Marine Dead Zones

Although some dead zones occur naturally, their size and frequency have increased dramatically due to intensive agriculture, urbanization, and climate warming. Fewer

than 50 were documented globally in 1950; today, more than 500 exist, with estimates suggesting the number may exceed 1,000. Source: World Economic Forum

Brief Outline: Marine Dead Zones

Introduction

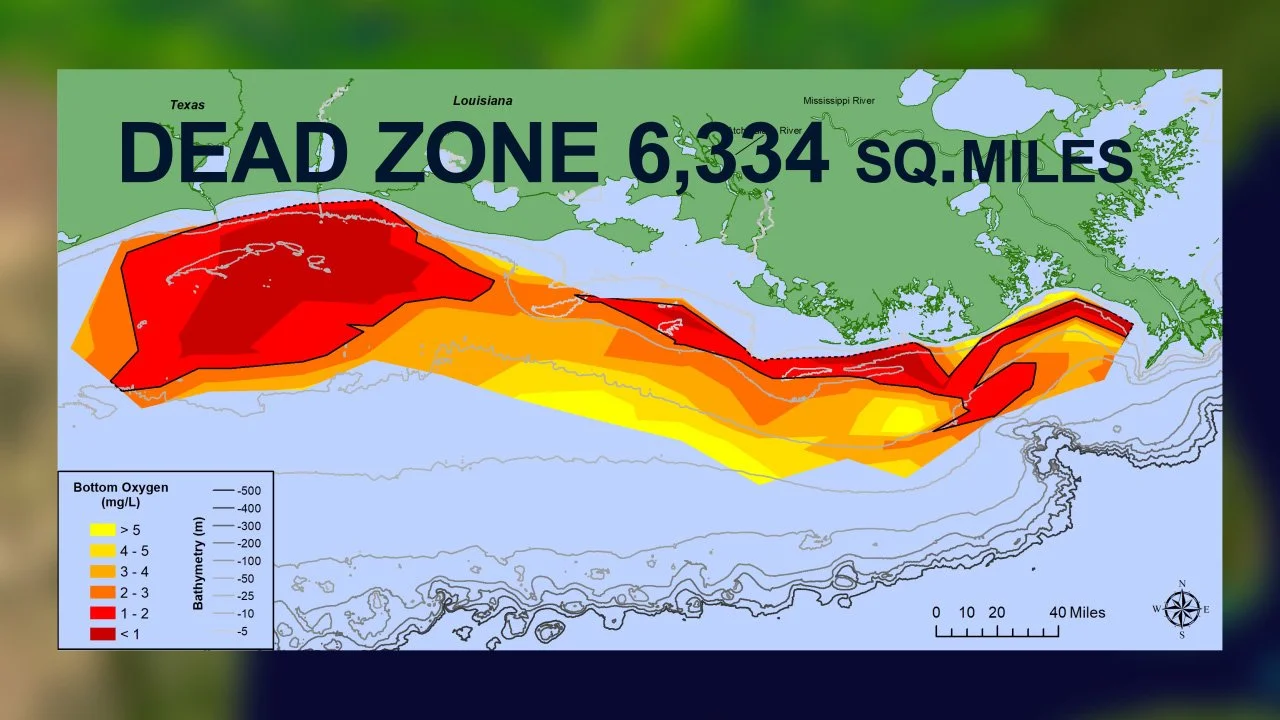

Seasonal dead zones form in coastal waters, especially in the Gulf of Mexico.

Productive fishing grounds become low-oxygen “wet deserts.”

Primary Causes

Eutrophication driven by excess nitrogen and phosphorus.

Nutrient sources include agriculture, sewage, and urban runoff.

Algal blooms deplete oxygen as they decompose.

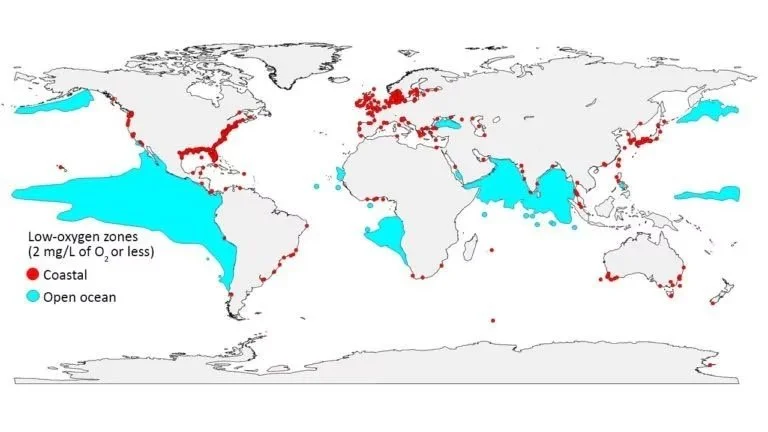

Global Expansion

Dead zones have increased rapidly since the 1970s.

Fewer than 50 documented in 1950; over 500 today worldwide.

Major Hotspots

Concentrated near river mouths and industrialized coasts.

Notable regions include the Gulf of Mexico, Baltic Sea, Chesapeake Bay, and East China Sea.

Ecological Impacts

Fish flee low-oxygen waters; bottom-dwelling species die.

Reduced growth, reproduction, and biodiversity.

Invasive species and diseases become more common.

Economic and Social Consequences

Fisheries become unstable and less profitable.

Increased risks to food security and coastal economies.

The 2021 Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone measures six thousand three hundred and thirty-four square miles. This was the largest dead zone in five years, making four million acres of habitat potentially unavailable to fish and bottom-dwelling species. Source NOAA Ocean Today

Seasonal Dead Zones in the Gulf of Mexico

Off the coast of Louisiana, summer dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico turn productive fishing grounds into low-oxygen “wet deserts.” Bottom-dwelling species struggle to survive, while shrimp and fish crowd the unstable edges of the dead zone. Fishermen must constantly move, increasing fuel costs and catching smaller, less valuable shrimp, making summer fisheries unpredictable and less profitable.

What Causes Marine Dead Zones

Dead zones form through eutrophication, driven by excess nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers, manure, sewage, and urban runoff. These nutrients fuel algal blooms that, when they die and decompose, consume oxygen in the water. The result is hypoxic or anoxic conditions that trigger biodiversity loss and periodic mass die-offs.

Growth of Dead Zones Worldwide

Although some dead zones occur naturally, their size and frequency have increased dramatically since the 1970s due to intensive agriculture, urbanization, and climate warming. Fewer than 50 were documented globally in 1950; today, more than 500 exist, with estimates suggesting the number may exceed 1,000.

Global Hotspots

Major dead zones occur near river mouths and industrialized coasts, including the Baltic Sea, Chesapeake Bay, and East China Sea. Rivers act as pathways for pollution, transporting nutrients that promote algal blooms and oxygen depletion.

Ecological Impacts

Low-oxygen conditions force fish and mobile animals to flee, while bottom-dwelling species often die. Oxygen loss slows growth, reduces reproduction, and alters behavior in stressed organisms. Over time, dead zones reduce biodiversity, eliminate seafloor communities, and allow invasive species and diseases to spread.

Economic and Food Security Risks

Recurring dead zones threaten major fisheries by reducing overall productivity and destabilizing catches. While nutrient pollution may temporarily boost some open-water species, long-term effects include fish prey loss, declining yields, and growing risks to coastal economies and global food security.

Coral Reefs

Coral reefs face serious threats from low oxygen levels and warming waters, which cause coral mortality. Hypoxia hampers coral growth and photosynthesis, leads to bleaching, and allows harmful algae and diseases to spread. Fish and invertebrates either flee, slow their metabolism, or move to areas with higher oxygen levels. Because reefs take decades to recover, repeated hypoxic events threaten fisheries, coastal protection, and tourism—vital sources of income for millions.

Jellyfish

Jellyfish, on the other hand, thrive in low-oxygen waters. Dead zones can become breeding grounds for jellyfish, leading to large blooms. These blooms disrupt food webs, damage fishing gear, reduce tourism, and contribute to climate change by breaking down jellyfish mucus, which releases carbon back into the atmosphere.

Seagrass Beds

Seagrass beds are harmed by excess nutrients, leading to algal overgrowth that blocks sunlight and creates hypoxic conditions. This stress and mortality reduce photosynthesis, stunt growth, and force reliance on inefficient anaerobic respiration. The loss of seagrass harms fisheries, water quality, coastal protection, and carbon storage—especially in tropical regions where local communities depend on seagrass-associated fish.

Mangrove Forest

Mangrove forests, naturally adapted to low oxygen levels, are increasingly threatened by pollution and poor land use. Shrimp farming, in particular, reduces water circulation and causes severe hypoxia. When oxygen levels fall too low, fish disappear, and ecosystems can collapse. Restoring mangroves and stopping destructive practices can help reduce eutrophication and revive local fisheries.

Summary

Marine dead zones are a growing global threat driven largely by nutrient pollution and climate change. Excess runoff fuels algal blooms that deplete oxygen, turning productive waters into low-oxygen “wet deserts” where biodiversity declines and fisheries become unstable. From the Gulf of Mexico to the Baltic Sea, these zones disrupt food webs, damage coral reefs, seagrass, and mangroves, and undermine coastal economies that depend on healthy oceans. Reducing nutrient pollution, improving land and water management, and addressing climate change are essential to restoring oxygen levels and protecting marine ecosystems for the future.