Salt Marshes

Where the Coast Breathes

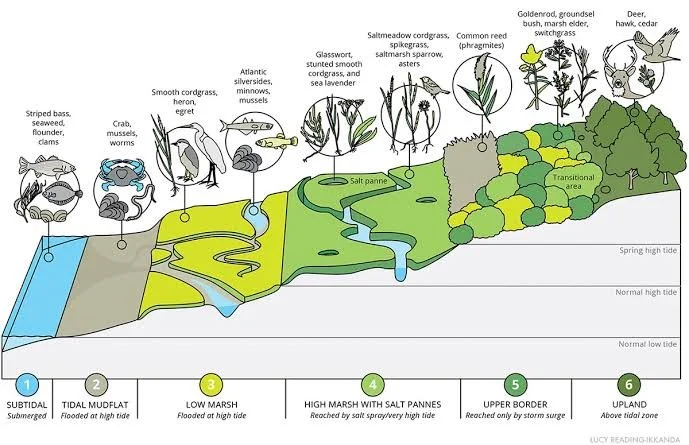

Marshes are divided into two distinct zones, with a minor elevation difference: low marsh, which floods daily at high tide, and the predominant high marsh, known for fine, low grasses that flood only

a few times each month. These wetland areas are especially vulnerable to projected climate change effects due to a legacy of widespread ditches and tidal restrictions that disrupt natural water flow.

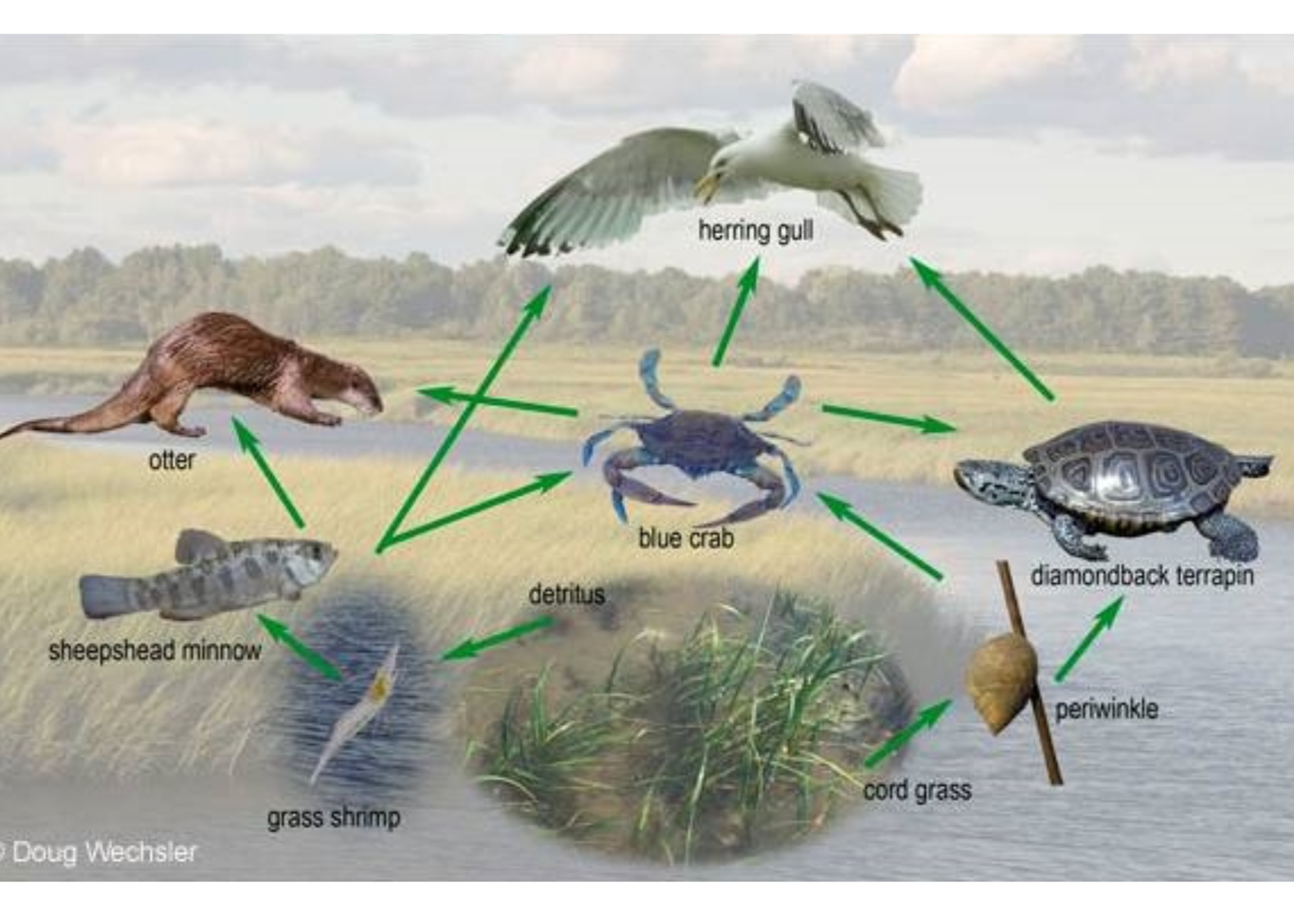

A salt marsh, a type of tidal marsh or tidal wetland, is a band of vegetation along coastal waters influenced by saltwater tidal flooding. It generally includes three ecologically distinct vegetation zones shown here as low marsh, high marsh, and upper border. These zones, largely defined by the frequency of saltwater tidal flooding, are determined by small differences in the marsh surface’s elevation relative to normal or mean high water. The salt marsh is dominated by dense stands of salt-tolerant plants such as grasses and shrubbery. Salt marshes play a large role in

the aquatic food web and the delivery of nutrients to coastal waters. They also support terrestrial animals and provide coastal protection (Credit: Lucy Reading-Ikkanda, Long Island Sound Study).

Salt Marshes: Where the Coast Breathes

At first glance, a salt marsh can seem quiet and empty. The land lies low and open beneath a wide sky, with winding creeks that glint silver in the sun. But pause for a moment, and the marsh comes alive. Grasses sway as the tide creeps in. A heron lifts silently from the shallows. Beneath the muddy surface, life stirs.

Salt marshes exist in a constant balance between land and sea. Twice a day, ocean tides flood these wetlands with salty water, then retreat hours later. This rhythm shapes one of the most productive ecosystems on Earth.

For centuries, salt marshes were dismissed as wastelands, muddy, mosquito-ridden places better drained than protected. Today, scientists recognize them as vital ecosystems, providing life, shielding coasts from storms, and playing a key role in fighting climate change.

A Landscape Built by Tides

Salt marshes form along sheltered coastlines, such as estuaries, lagoons, and bays, where waves

are gentle enough for fine sediments to settle. Over time, layers of mud mix with decaying plant matter to form peat, a dense, spongy soil that can be several feet thick.

Life here is anything but easy. Plants must endure salty water, intense heat, shifting sediments, and soils starved of oxygen. Yet salt marsh vegetation has evolved remarkable adaptations. Some species excrete excess salt through specialized glands in their leaves. Others grow shallow but extensive root systems that anchor them against tides while drawing oxygen from the air.

Because flooding varies across the marsh, the landscape organizes itself into natural zones. Lower areas, submerged daily, host short, tough grasses. Higher ground floods less often and supports taller, more diverse plants. Together, these zones create a living mosaic shaped entirely by water.

A Global Ecosystem, Quietly Vast

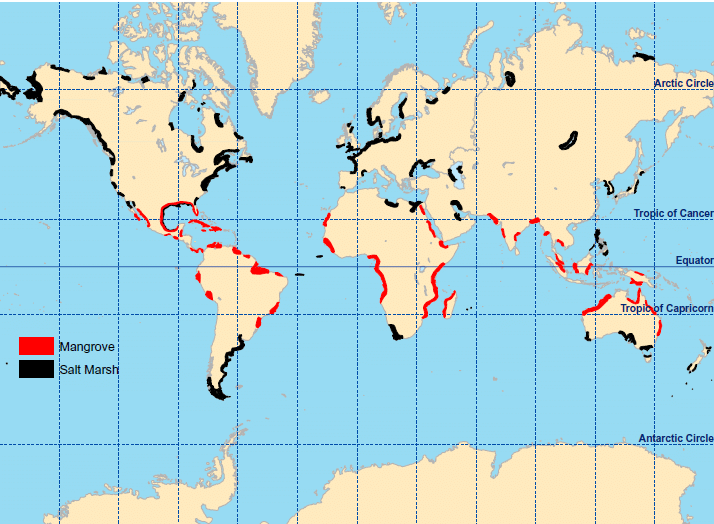

Salt marshes are found on every continent except Antarctica, stretching from temperate coastlines to high latitudes. Scientists estimate they cover anywhere from 5.4 to nearly 100 million acres worldwide, though the true number remains uncertain due to limited mapping in remote regions.

More than 60% of the world’s tidal marshes are concentrated in just three countries, the United States, Canada, and Russia, yet only a fraction of these wetlands receive formal protection. Many remain vulnerable to development, pollution, and rising seas.

Nature’s Coastal Shield

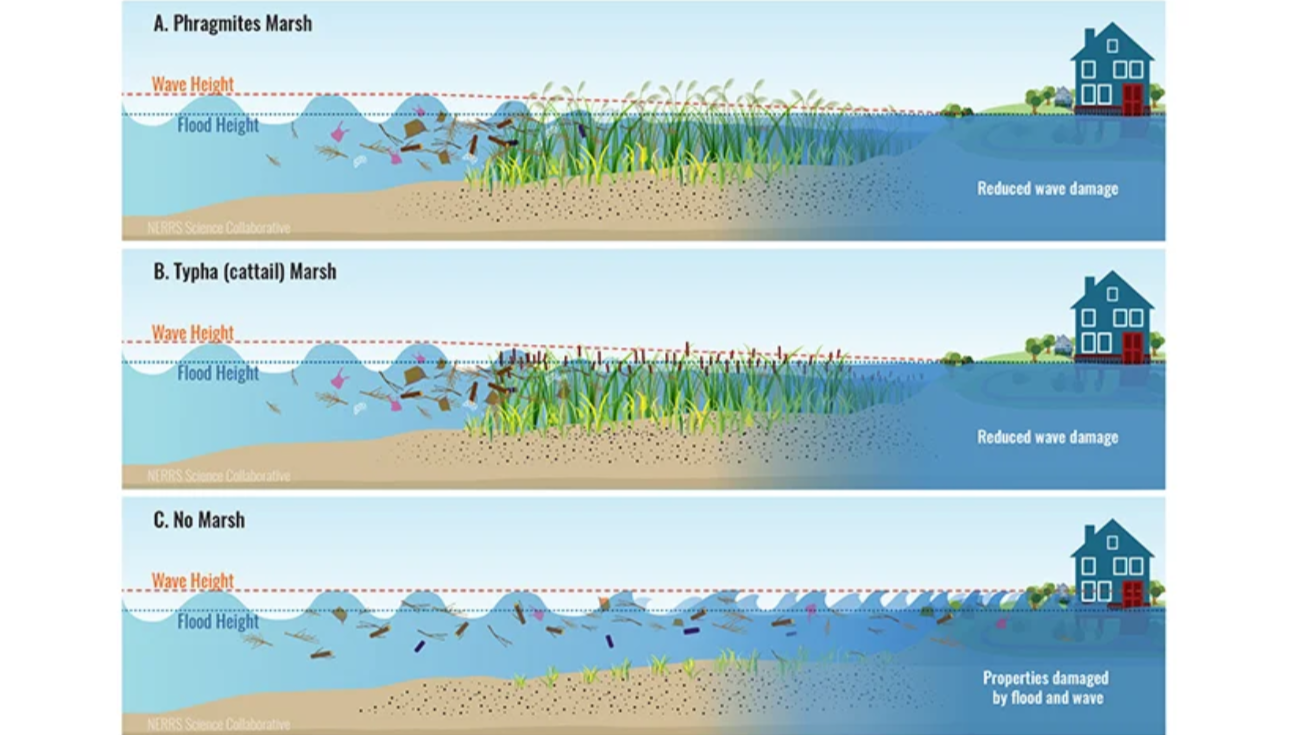

When storms strike, salt marshes reveal their quiet strength.

Dense grasses bend and sway, absorbing wave energy that would otherwise crash directly into shorelines. Thick peat soils act like giant sponges, soaking up floodwaters during storms and high tides. Just one acre of salt marsh can absorb up to 1.5 million gallons of water, helping reduce flooding in nearby communities.

Studies show that salt marshes can reduce storm-related property damage by as much as 20%. Along U.S. coastlines alone, coastal wetlands provide an estimated $23 billion in flood protection every year, a natural service that no seawall can replicate without enormous cost.

As water moves through the marsh, it slows, spreads out, and filters through vegetation and soil. Pollutants, from fertilizers to heavy metals, are trapped and broken down before reaching the ocean. In this way, salt marshes quietly clean the water that sustains coastal fisheries and recreation.

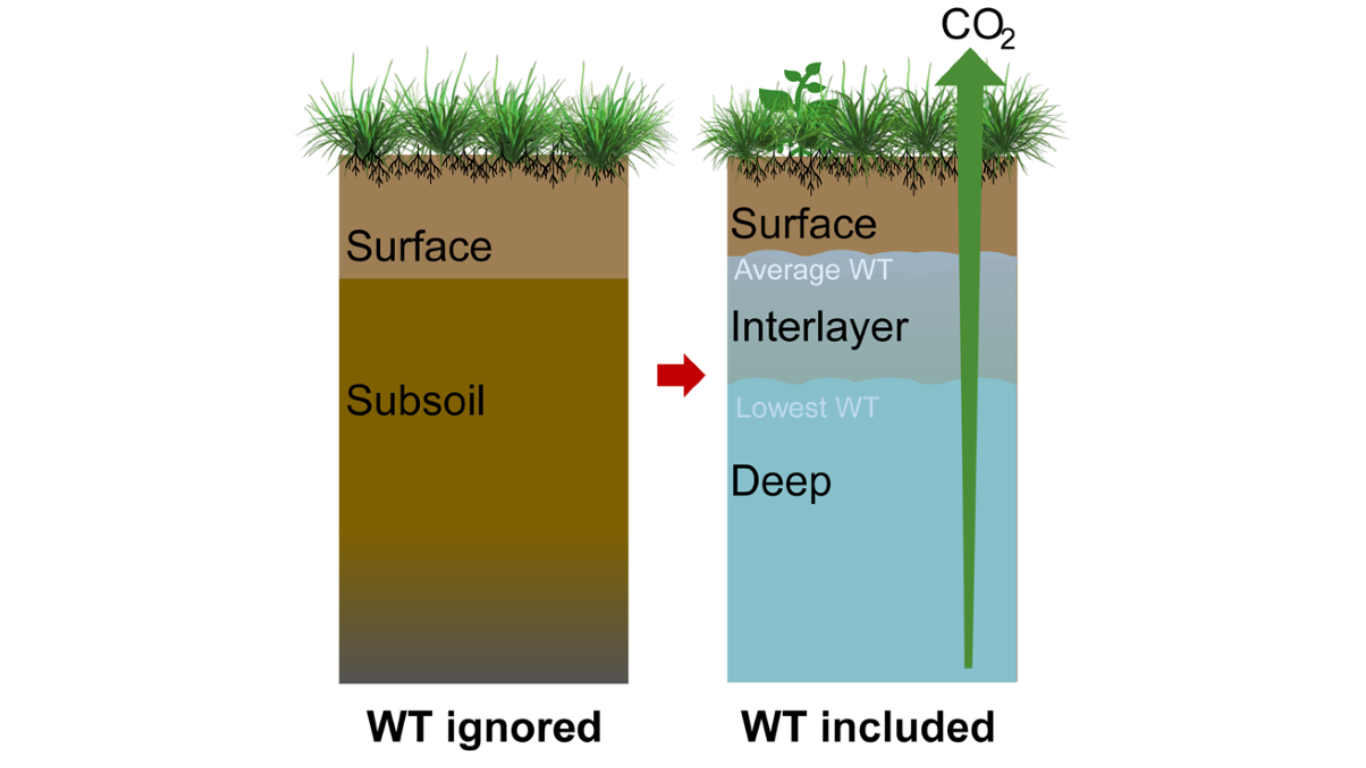

Carbon Buried Beneath Our Feet

Salt marshes do more than protect the coast. They help stabilize the planet’s climate.

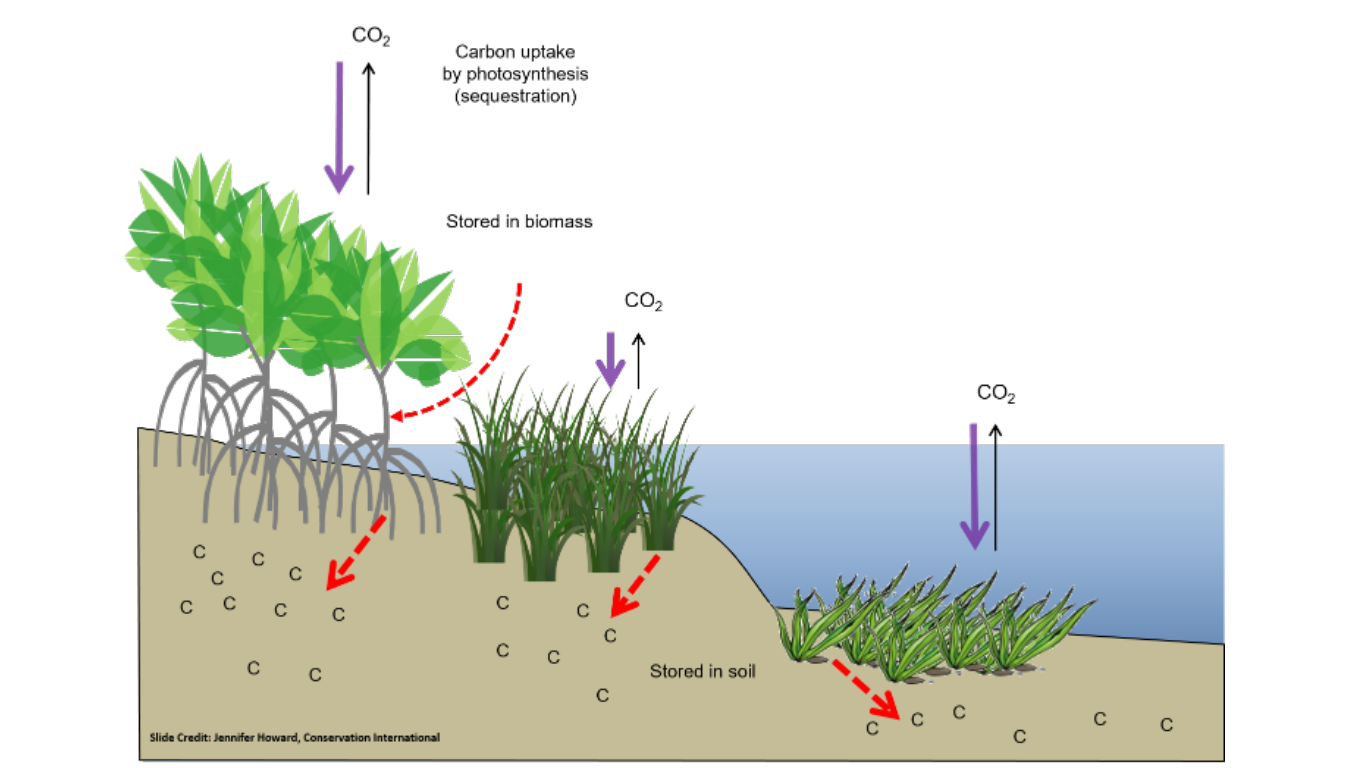

These wetlands are part of a group known as blue carbon ecosystems, which also includes mangroves and seagrass meadows. While marsh plants capture carbon through photosynthesis,

their greatest climate power lies underground. As plants die, their remains are buried in waterlogged soils where oxygen is scarce. Decomposition slows to a crawl.

Over centuries, this process builds deep layers of carbon-rich peat. An estimated 95% of the

carbon stored in salt marshes lies below ground, locked away for hundreds or thousands of years. Per acre, salt marshes can store more carbon than tropical rainforests, making their preservation a critical climate solution.

A Nursery for the Sea

At low tide, shallow creeks carve delicate patterns through the marsh, and with the returning water, life follows.

Juvenile fish, shrimp, and crabs shelter among the grasses, safe from predators that roam open waters. Here, they feed and grow before migrating offshore. More than 75% of commercially important fisheries species depend on salt marshes at some stage of their lives.

Above the waterline, birds reign. Herons stalk the shallows. Egrets spear fish with lightning speed. Migratory species pause here during epic journeys, refueling before continuing across continents. Mammals hunt along the edges, while insects and plankton form the invisible foundation of the

food web.

Salt marshes are not isolated systems. They fuel entire coastal ecosystems, exporting nutrients and energy far beyond their muddy borders.

A Different Kind of Coastline

For travelers, salt marshes offer a quieter coastal experience. Kayakers glide through narrow creeks framed by grasses. Birdwatchers scan wide horizons for flashes of wings. Boardwalks invite slow exploration rather than hurried consumption.

In regions like the southeastern United States, marshes underpin thriving nature-based tourism economies. By stabilizing shorelines and improving water quality, they also protect beaches, coral reefs, and seagrass beds that draw millions of visitors each year.

A Vanishing Landscape

Despite their value, salt marshes are disappearing.

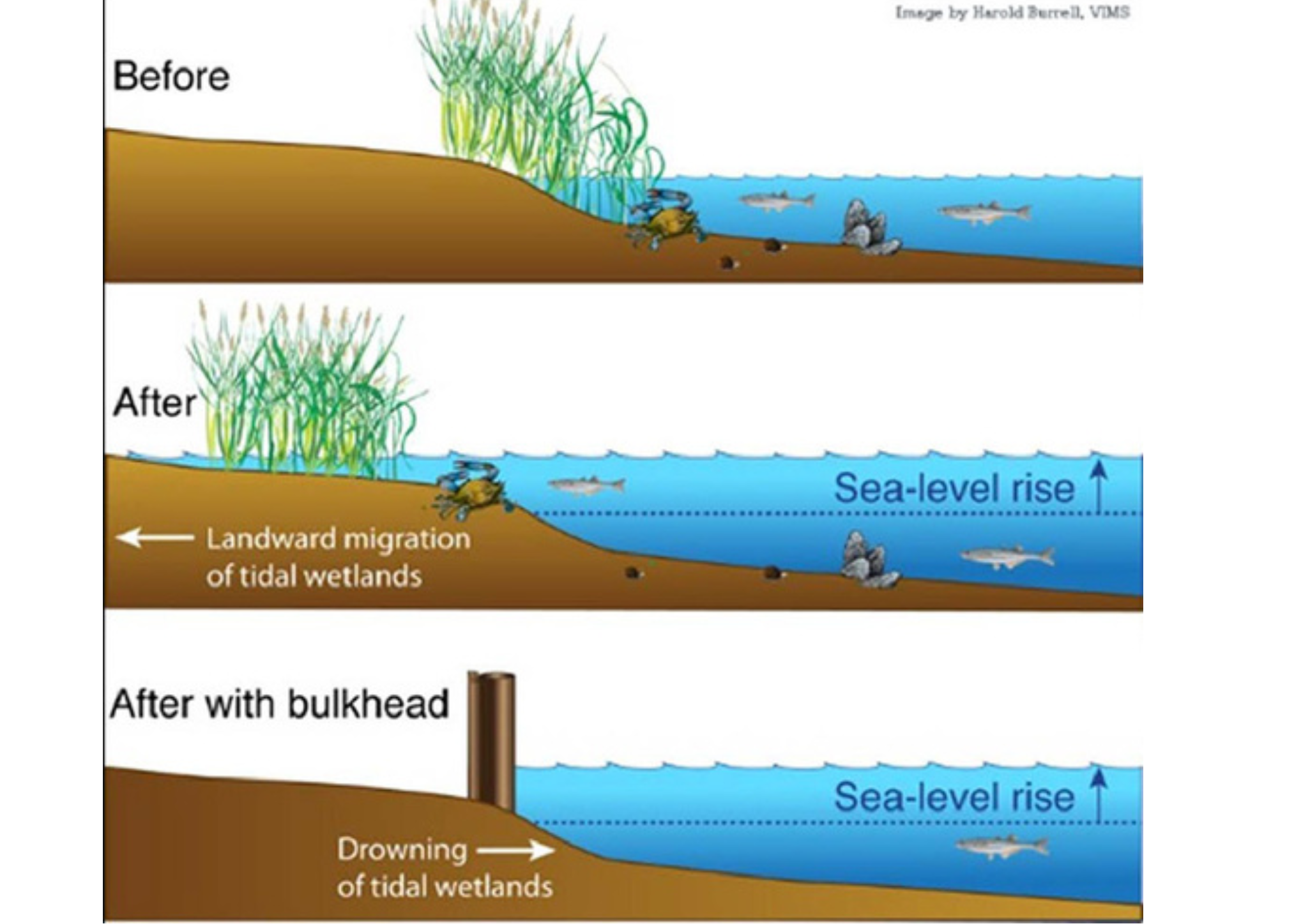

Globally, scientists estimate that 25% - 50% of historical salt marsh coverage has already been lost. Between 2000 and 2019 alone, the planet lost roughly 560 square miles of marsh, about one soccer field every hour.

The causes are many. Rising seas are drowning marshes faster than they can build new soil. Coastal development blocks their natural migration inland, trapping them between advancing water and hard infrastructure, a process known as coastal squeeze. Pollution weakens soils and vegetation. Invasive species unravel food webs.

If current trends continue, scientists warn that more than 90% of the world’s salt marshes could be submerged or lost by the end of this century.

Rebuilding the Living Coast

Yet, there is hope!

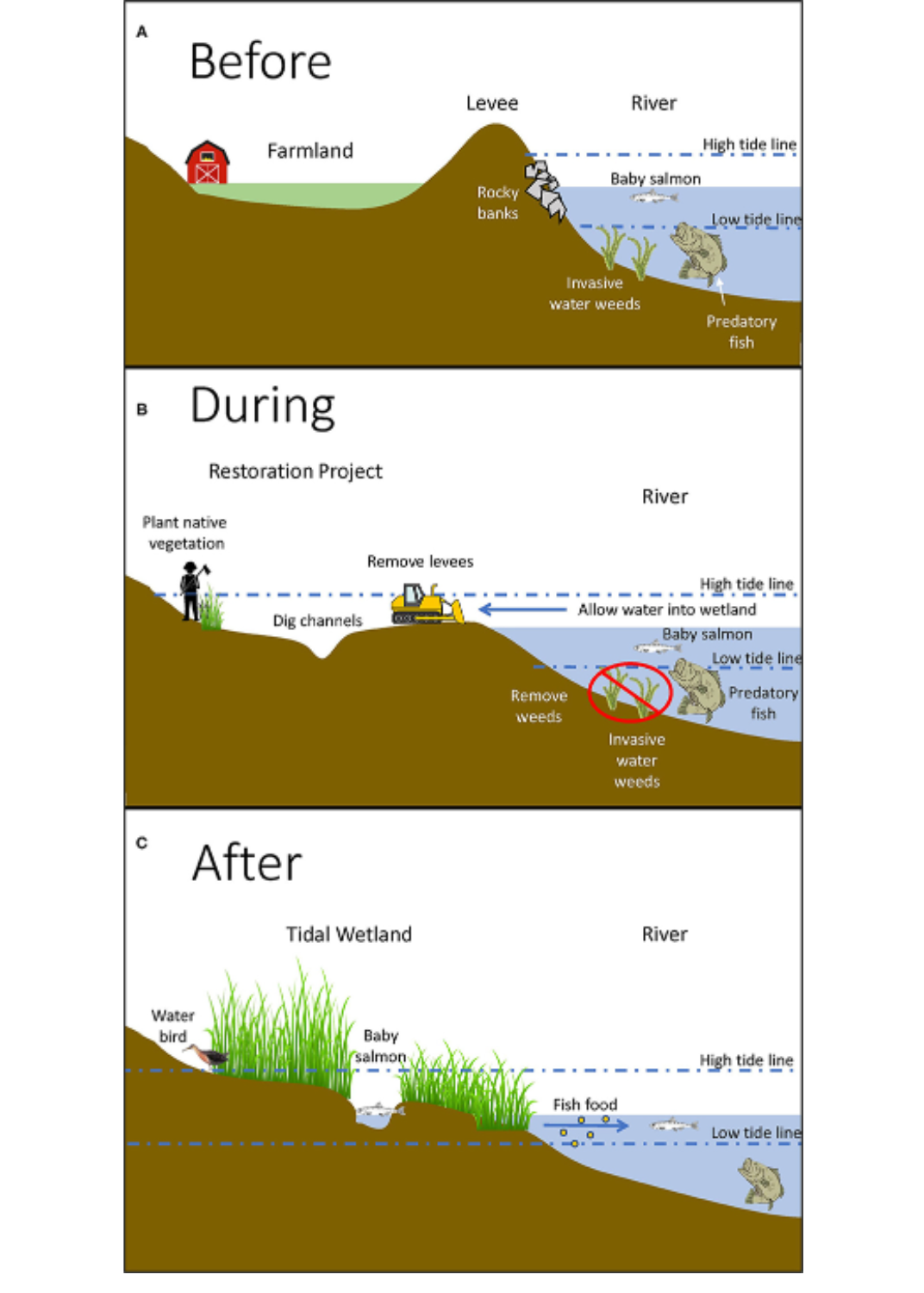

Around the world, restoration projects are breathing life back into degraded marshes. Engineers and ecologists are removing dikes and seawalls to restore natural tidal flow. Sediment is being added to raise the sinking land. Native grasses are replanted, and invasive species are carefully managed.

Large-scale efforts, such as the transformation of former industrial salt ponds into wetlands,

are proving that salt marshes can recover when given space and time. These restored landscapes once again store carbon, protect coastlines, and support wildlife.

The Quiet Power of the Marsh

Salt marshes rarely demand attention. They do not dazzle like coral reefs or tower like rainforests. Instead, they work quietly, absorbing storms, filtering water, feeding the sea, and locking away

carbon grain by grain.

Standing at the edge of a marsh as the tide returns, it becomes clear: this is not empty land. It is breathing land. And in a warming, rising world, the future of our coasts may depend on how well we learn to protect these muddy, magnificent places where land and sea meet.