Rising Seas, Vanishing Worlds:

How Sea-Level Rise Is Reshaping Marine Ecosystems

The remnants of 300-year-old trees, which once stood tall but are now all but drowned, are attributable to sea-level rise. Credit:60 Minutes.au

The rising sea surface is primarily driven by thermal expansion of warming seawater and by melting glaciers/ice sheets due to human-caused climate change.

Key Takeaways:

Sea levels are rising rapidly due to melting ice sheets, warming oceans, and human water use.

Nearly half of global sea-level rise has happened in just the last 30 years.

Antarctica and Greenland are losing hundreds of billions of tons of ice each year, accelerating the problem.

Oceans absorb most of Earth’s excess heat, causing water to expand and raise sea levels.

Without major emission reductions, sea levels could rise over 3 feet by 2100.

Rising Sea Levels

Rising sea levels are one of the most dramatic consequences of climate change, fueled by the melting of glaciers and ice sheets and the thermal expansion of seawater as it absorbs more heat. Human activities, like groundwater depletion, also add to the problem by contributing additional water to

our oceans.

The Science Behind Rising Sea Levels

Since 1880, global sea levels have climbed by 21–24 cm (8–9 inches), with nearly half of that rise occurring in just the last 30 years. If greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current pace, the IPCC warns we could see a rise of up to 1.1 meters (3.6 feet) by 2100.

The ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland are melting at an alarming rate—Antarctica loses 219 billion tons of ice every year, while Greenland contributes 280 billion tons annually, both significantly driving sea level rise (Nature, 2018). Meanwhile, the oceans are absorbing 90% of global warming, with thermal expansion responsible for up to half of the rising water levels.

A mangrove forest in Shenzhen Bay, China. At stake are the marine ecosystems that anchor life at the sea's edge and support biodiversity, fisheries, and natural defenses against storms. Photo source: Xinhua/Shutterstock

Along the world’s coastlines, change is arriving not as a sudden catastrophe but as a steady, relentless advance. With every passing decade, the ocean creeps higher, swallowing beaches grain by grain, flooding wetlands inch by inch, and pressing saltwater deeper into places that once held fresh life. Sea-level rise—driven primarily by the thermal expansion of warming oceans and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets—is now one of the most pervasive and transformative consequences of climate change. Its effects extend far beyond flooded shorelines and threatened coastal communities.

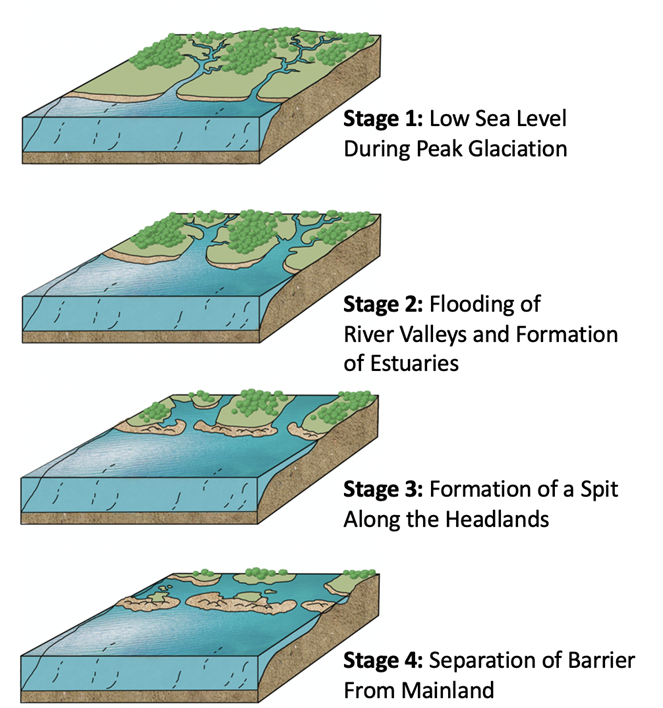

Barrier Island Development. Figure by Jeremy Patrich is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

As sea levels rise, the delicate balance that sustains them begins to unravel, setting off cascading effects across food webs and human economies alike.

Coastal ecosystems exist in a narrow zone where land and ocean meet, shaped by tides, waves, and shifting sediments. Mangrove forests, salt marshes, seagrass meadows, sandy beaches, estuaries, and coral reefs are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth. They serve as nurseries for fish, nesting sites for turtles and seabirds, and feeding grounds for countless species. Yet these ecosystems are also among the most vulnerable.

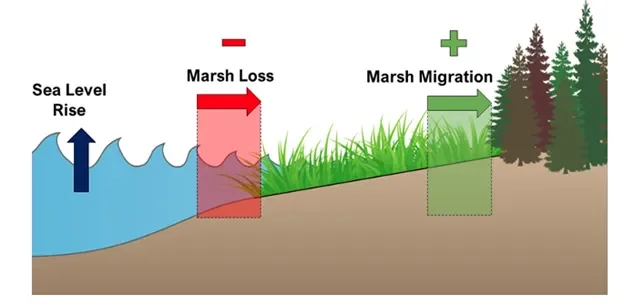

As sea levels rise, lower-elevation marshes are lost to open water, and upper-elevation ecosystems may transition to marsh. Photography on the right show a home with a harden shoreline in Beaufort, SC that abuts the salt marsh . Credit Carolina Wetland Association

One of the most immediate consequences of sea-level rise is habitat loss through inundation and erosion.

Low-lying coastal wetlands and intertidal zones are particularly exposed. Salt marshes and mangroves can survive rising seas only if they can migrate landward, raising elevation through sediment accumulation and organic growth. In many regions, however, this natural migration is blocked by seawalls, roads, and coastal development—a phenomenon scientists call “coastal squeeze.” Trapped between rising water and hardened shorelines, wetlands drown in place. When they disappear, so do the critical services they provide: carbon storage, water filtration, and shelter for juvenile fish and crustaceans that later populate offshore waters.

Powerful storms over several days carved away large sections of beach in North Wildwood, leaving dunes collapsed, vegetation uprooted, and the shoreline dramatically narrowed. Credit: Wildwood Video Archive

Beaches, too, are eroding under the pressure of higher seas.

For species such as sea turtles, which rely on narrow bands of sandy shoreline to lay their eggs, the loss of nesting habitat can be devastating. As beaches shrink or are repeatedly flooded by high tides and storm surges, nests are washed away or inundated with saltwater, reducing hatchling survival. Shorebirds that depend on undisturbed beaches for feeding and nesting face similar pressures, as their habitat narrows and human disturbance intensifies in the remaining areas.

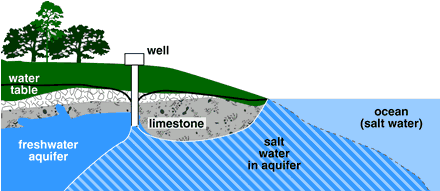

Salt water intrusion as a result of sea level rise. Credit: H20 care

Rising seas also drive saltwater intrusion.

Saltwater intrusion is the inland movement of seawater into freshwater ecosystems and underground aquifers. Estuaries, where rivers meet the sea, are naturally brackish, but increasing salinity can push these systems beyond the tolerance of many plants and animals. Freshwater marsh vegetation may die off, replaced by salt-tolerant species or open water, fundamentally altering habitat structure. Inland, saltwater intrusion into groundwater threatens freshwater supplies for both ecosystems and coastal communities. As freshwater sources become contaminated, the ripple effects extend to terrestrial wildlife, agriculture, and human health.

American Alligators will occasionally venture into saltwater, but lack the specialized salt glands of crocodiles and must return to freshwater to rebalance salt levels. Photo Credit National Park Service

Altered species distributions are occurring due to sea level rise.

For marine species, these physical changes translate into profound biological consequences. Altered species distributions are becoming increasingly common as organisms respond to shifting salinity, temperature, and habitat availability. Fish and invertebrates may move poleward or into deeper waters in search of suitable conditions, disrupting long-established predator–prey relationships. Some species adapt quickly, while others—particularly those with limited mobility or specialized habitat requirements—struggle to keep pace. The result is a reshuffling of ecosystems, with winners and losers, and growing uncertainty for fisheries that depend on predictable species distributions.

Hurricane Sandy flooded over 300,000 coastal homes in the US, worth $120 billion in 2012. The flooding of 36,000 homes was attributed to sea level rise. Photo credit Master Sgt. Mark Olsen, AP

Increased intensity of coastal storms compounds the stress of sea-level rise.

Higher baseline sea levels amplify storm surges, allowing waves and floodwaters to penetrate farther inland during hurricanes, cyclones, and nor’easters. These events can strip away vegetation, scour seafloor habitats, and deposit sediment, which can smother seagrass beds and coral reefs. While many coastal ecosystems are adapted to occasional disturbance, the growing frequency and severity of storms leave little time for recovery. Repeated impacts can push ecosystems past ecological tipping points, transforming vibrant habitats into degraded landscapes.

In 2015, American Samoa experienced significant coral death due to a severe global bleaching event, primarily driven by unusually high sea temperatures linked to climate change and El Niño, causing widespread bleaching and mortality, with some areas seeing up to 80% coral loss. Photo Credit National Marine Sanctuary American Samoa

The loss of coral reefs reverberates far beyond the reef itself.

These ecosystems occupy less than one percent of the ocean floor yet support an estimated quarter of all marine species. When reefs decline, fish populations drop, coastal fisheries suffer, and communities that depend on reef-based tourism and food security face growing hardship. Reefs also act as natural breakwaters, absorbing wave energy and protecting coastlines from erosion. Their degradation leaves shorelines more exposed, reinforcing the destructive cycle of sea-level rise and storm damage.

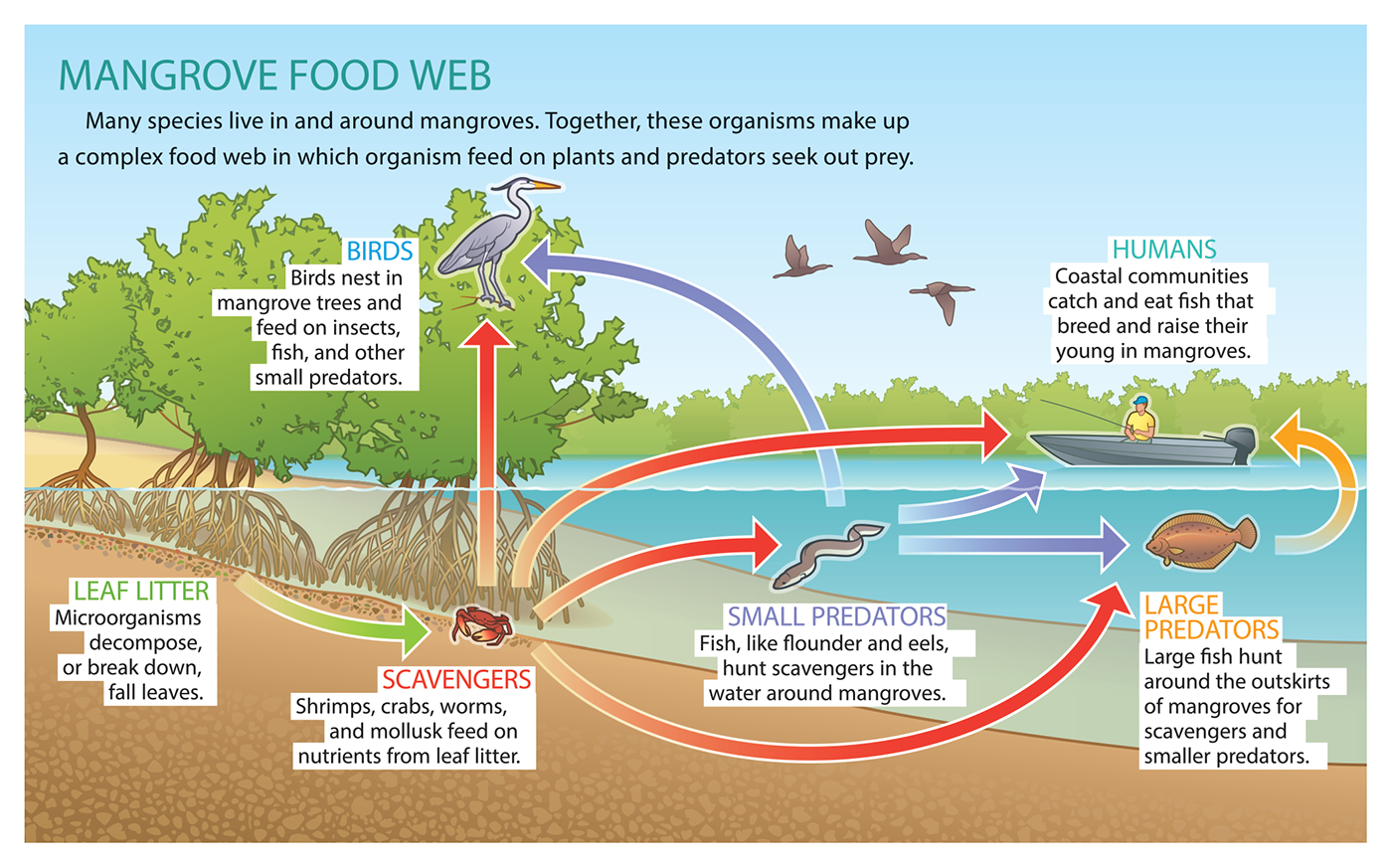

Sea level rise can threaten the mangrove ecosystem, with significant impacts on biodiversity and on fish nurseries, affecting fish populations and community food sources. Credit Behance and Eyewash

Across coastal ecosystems, the cumulative effects of sea-level rise are cascading through food webs.

When nursery habitats like mangroves and marshes disappear, fewer juvenile fish survive to adulthood, reducing populations offshore. Predators lose prey, fishery yields decline,a nd biodiversity erodes. These changes are often subtle at first, unfolding over years rather than days, but their long-term consequences are profound. Ecosystems that once buffered coastlines, supported livelihoods, and teemed with life become simplified and less resilient.

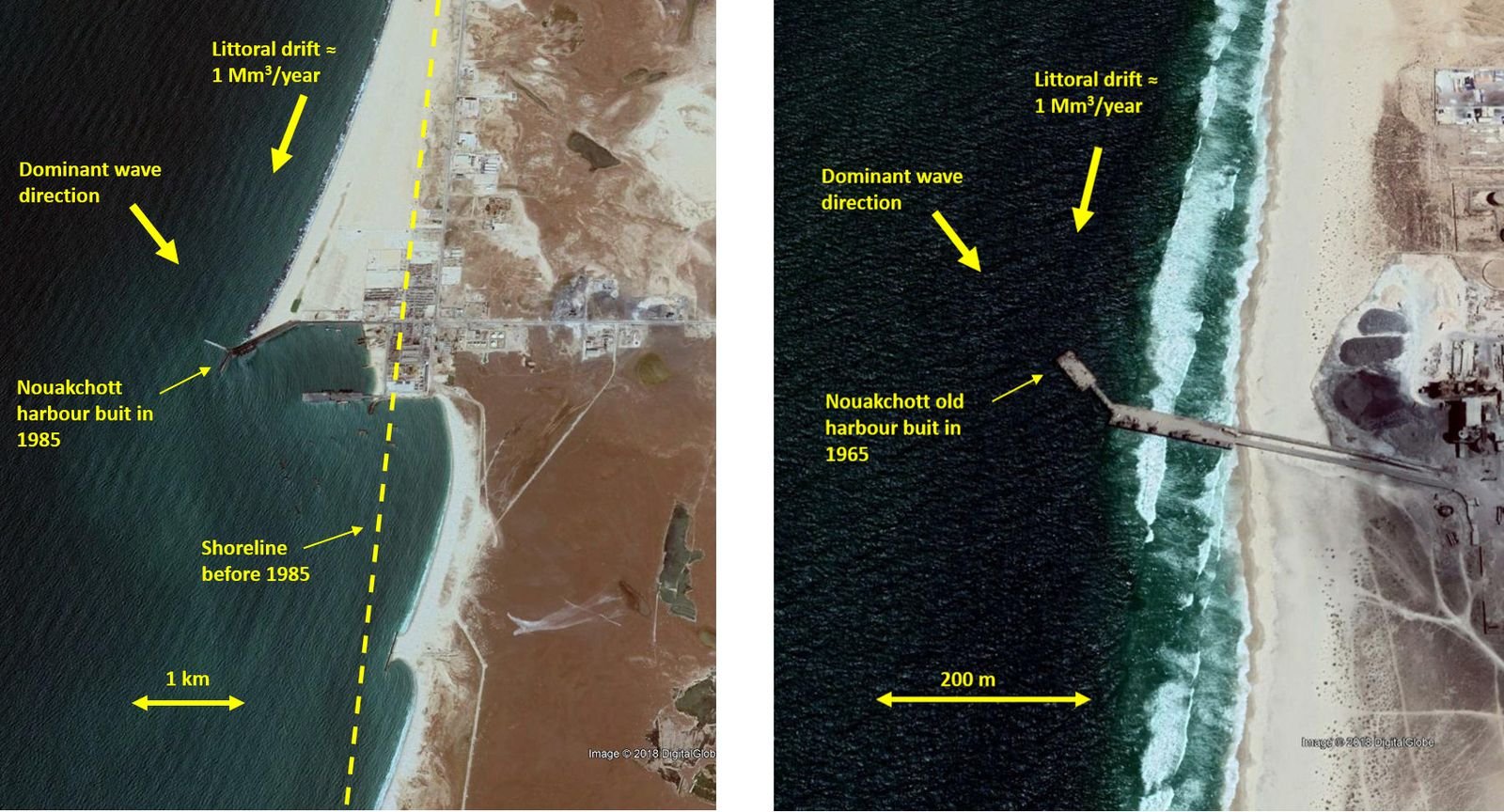

Left: The new seaport of Nouakchott (Mauritania) built in 1985 (image October 2017). Right: The (smaller) old port of Nouakchott, built in 1965. The port blocks were placed to protect the old Nouakchott harbor against a long shore current perpendicular to the dominant wave direction. The result is massive accretion at the updrift side and equivalent massive erosion at the downdrift side of the harbor. Photo credit: Coastal Wiki

Human activity plays a critical role in shaping these outcomes.

Coastal development, dredging, and shoreline armoring can accelerate erosion and prevent natural adaptation. At the same time, restoration and conservation efforts offer pathways for resilience. Protecting remaining wetlands, restoring mangroves, allowing rivers to deliver sediment to deltas, and redesigning coastal infrastructure to work with—not against—natural processes can help ecosystems adjust to rising seas. Such “nature-based solutions” not only support biodiversity but also provide cost-effective protection for coastal communities.

In the quiet retreat of a salt marsh, the collapse of a turtle nest, or the bleaching of a coral reef, sea-level rise leaves its signature. These are not isolated losses but chapters in a larger narrative—one that reminds us that the boundary between land and sea is alive, dynamic, and deeply vulnerable. Protecting it will require not only scientific understanding, but the collective will to recognize that the health of the oceans is inseparable from the future of life on Earth.