Deep-sea trawling have fishing processing facility below deck and may spend up to 300 days at sea

Source:Min.news

Overfishing:

Causes, Consequences, and Solutions

The Hidden Cost of Overfishing Our Oceans

Overfishing is an urgent problem threatening marine life, biodiversity, and the future of our food supply. It happens when we catch fish faster than they can reproduce, leaving populations in decline and ecosystems in chaos. Since industrial fishing took off in the 1950s, practices like bottom trawling and long lining have worsened the situation, depleting fish stocks and damaging marine habitats. With millions relying on fisheries for food and income, sustainable fishing is more important than ever.

Key Takeaway

Overfishing is not inevitable; it is a management failure that can be reversed.

With strong governance, informed consumers, and global cooperation, ocean ecosystems can recover and sustain future generations.

1. The Core Problem

Overfishing occurs when fish are caught faster than they can reproduce, disrupting marine ecosystems.

Industrial fishing technology has accelerated exploitation, causing the number of overfished stocks to triple since the 1970s.

Today, more than 35% of global fisheries are fished at biologically unsustainable levels.

2. Ecological Impacts

Populations of major species such as tuna, cod, and sharks have declined by up to 90% in some regions.

Bycatch kills millions of non-target species, including sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals.

Loss of key species destabilizes food webs and accelerates coral reef degradation.

3. Human Consequences

Over 3 billion people depend on seafood as a primary protein source.

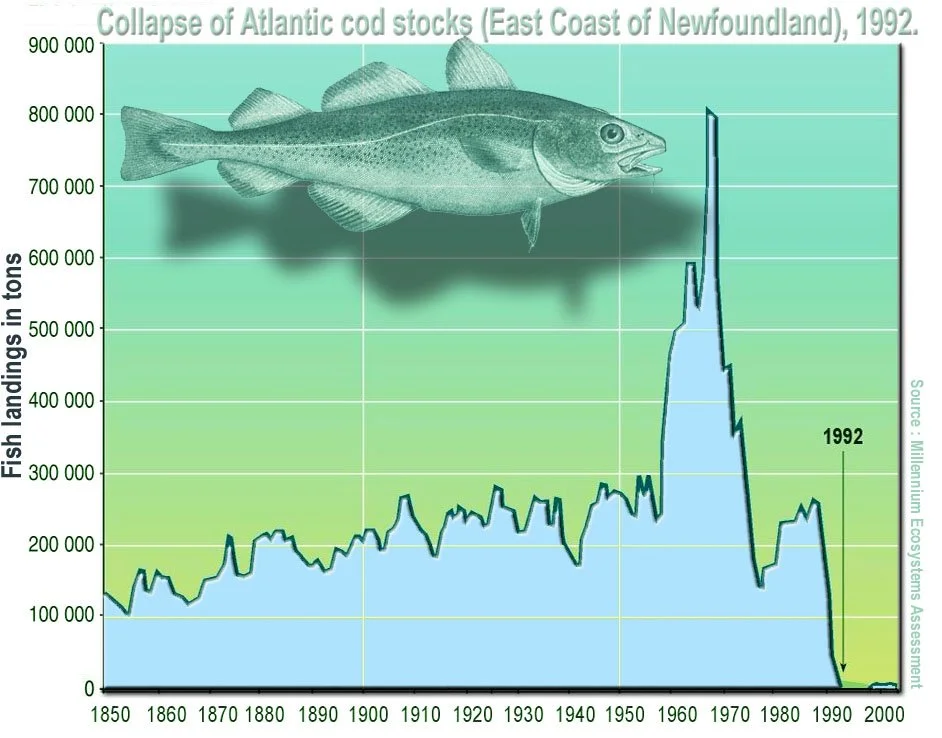

Fishery collapses can devastate communities, as seen in the Grand Banks cod collapse.

Declining fisheries threaten global food security and coastal economies.

4. Drivers of Overfishing

Excess fishing capacity fueled by government subsidies and advanced technology.

Weak governance and limited enforcement, especially on the high seas and in developing regions.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing accounts for up to one-third of global catch.

5. Solutions and Hope

Science-based fisheries management, including catch limits and adaptive controls, can rebuild stocks.

Successful examples include the U.S., Iceland, and New Zealand.

Ending harmful subsidies is key to reducing overcapacity and environmental damage.

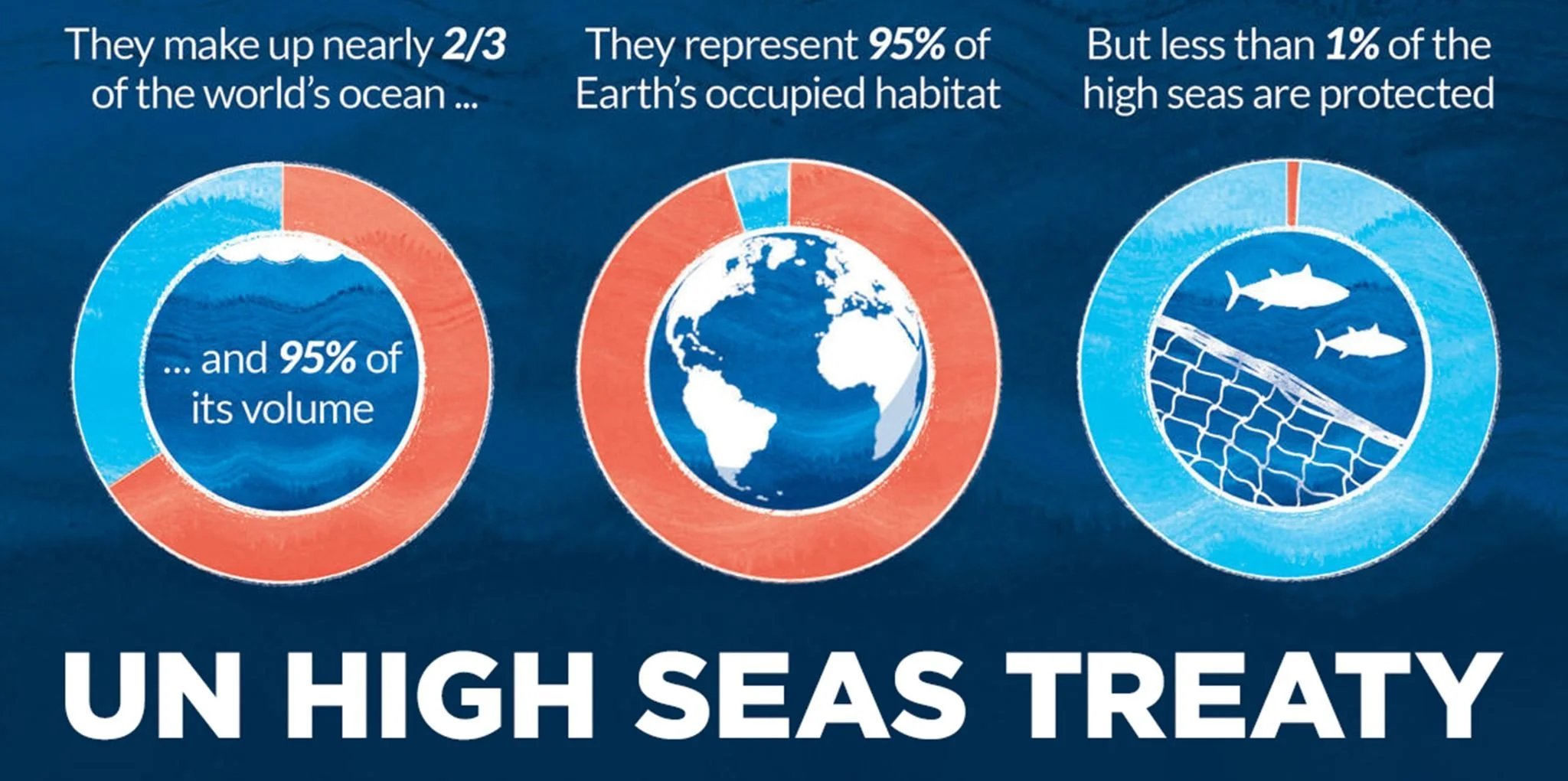

UN High Sea treaty went in force in January 2026 creates the first legally binding framework to protect marine life in the high seas

Sustainable seafood certifications (Marine Stewardship Council, Friend of the Sea) guide responsible choices.

Consumer tools like Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch and NOAA FishWatch empower informed decisions.

Global Fishing Watch increases transparency by tracking fishing activity worldwide.

Overfishing occurs when fish are harvested faster than they can reproduce, disrupting marine ecosystems and threatening biodiversity, food security, and coastal livelihoods worldwide. Fishing itself is not inherently harmful; the crisis arises when extraction exceeds ecological limits. Over the past 50 years, the number of overfished stocks has tripled. Today, roughly 35.5% of global fish stocks are exploited at biologically unsustainable levels—three times the rate seen in the 1970s.

Industrial fishing has intensified this pressure. Modern fleets use sonar, GPS, and massive trawl nets—some large enough to “swallow a Boeing 747”—to locate and capture fish with unprecedented efficiency. As a result, populations of iconic species such as tuna, cod, and sharks have declined by as much as 90% in some regions. Bycatch remains a major issue, with an estimated 40% of global catch consisting of non-target species, including sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals, often discarded dead or dying.

Fishing boats setting sail in the East China Sea. Crews are gone for months at a time, and they — and the vessels’ owners — can make a fortune from their catch. Article in the The Times “Squid game: how Chinese fishing fleets are threatening the Galapagos”. Adam Vaughan, Environment Editor, October 06 2022, The Times.

Photo: YAO FENG/VCG/GETTY IMAGES

Causes of Overfishing

Approximately four million fishing vessels now operate globally, many equipped with advanced technology that dramatically increases catch capacity. In many regions—particularly in developing countries and on the high seas—limited resources, weak governance, and insufficient international cooperation hinder effective fisheries management.

Government subsidies further exacerbate the problem. Billions of dollars are spent annually to keep fishing economically viable despite declining stocks, encouraging excess capacity and masking true environmental costs. The global fishing fleet is estimated to be up to 2.5 times larger than what oceans can sustainably support. The United Nations 2030 Agenda explicitly calls for the elimination of harmful fisheries subsidies.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing compounds these challenges. An estimated 11–26 million tons of fish—representing 14–33% of reported global catch—are taken illegally each year. Even where regulations exist, underreporting, out-of-season fishing, and weak enforcement remain common, particularly as global seafood demand has quadrupled over the past half-century.

Consequences for People and Ecosystems

The impacts of overfishing extend far beyond the ocean. More than three billion people rely on seafood as their primary source of animal protein, making food security increasingly fragile. Economic collapse can be swift and devastating, as demonstrated by the 1992 collapse of Canada’s Grand Banks cod fishery, which left over 35,000 people unemployed almost overnight.

Ecologically, overfishing undermines essential ecosystem services. The removal of herbivorous fish allows algae to overwhelm coral reefs, leading to reef degradation, biodiversity loss, and reduced coastal protection from storms and erosion.

The Atlantic fishery abruptly collapsed in 1993 after overfishing from the late 1950s and an earlier partial collapse in the 1970s. It is possible to recover to historical, sustainable levels by 2030.

Source: Lamiot

Solutions and Paths Forward

Overfishing is solvable. Many fisheries have successfully adopted science-based management tools, including catch quotas, size and bag limits, seasonal closures, and marine protected areas. Evidence shows that the most effective strategies combine spatial protections with adaptive catch limits, such as Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs), which allocate a share of the total allowable catch and adjust annually based on stock health.

In the United States, the Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act has helped prevent stock collapses and rebuild depleted fisheries. First passed in 1976, the MSA fosters the long-term biological and economic sustainability of marine fisheries. Its objectives include preventing overfishing, rebuilding overfished stocks, increasing long-term economic and social benefits, ensuring a safe and sustainable supply of seafood, and protecting habitats that fish need to spawn, breed, feed, and grow to maturity. Iceland, New Zealand, and the U.S. demonstrate that strong governance and science-driven management can restore fisheries and ensure long-term sustainability. However, while these limits govern the fishing in territorial waters, until recently, there was little protection for much of the ocean between nations.

Eliminating harmful subsidies is also critical. Studies show that deep-sea bottom trawl fleets receive roughly US$152 million annually in subsidies—primarily fuel support—despite operating at a net economic loss. Removing these subsidies would reduce overfishing, lower carbon emissions, and protect some of the planet’s most fragile marine habitats.

The UN High Seas Treaty is a landmark international instrument that entered into force in January 2026, establishing the first legally binding framework for the protection of marine life in the high seas (areas beyond national waters). Adopted in 2023 and entered into force in January 2026.

Source: Bannon

The UN High Seas Treaty, formally known as the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, entered into force in January 2026, creating the first legally binding framework to protect marine life in the high seas—areas beyond national borders that make up nearly two-thirds of the global ocean. Adopted in 2023, the treaty closes major gaps in ocean governance by enabling the creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in international waters and requiring environmental impact assessments for potentially harmful activities such as deep-sea mining.

The agreement also establishes rules for sharing benefits from marine genetic resources and strengthens capacity building, helping developing countries access technology, science, and training for ocean stewardship. Ratified by 60 countries, the treaty provides a critical legal pathway to safeguard biodiversity in previously unprotected waters and is a cornerstone of the global goal to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030, marking a new era of collective responsibility for the health of the world’s oceans.

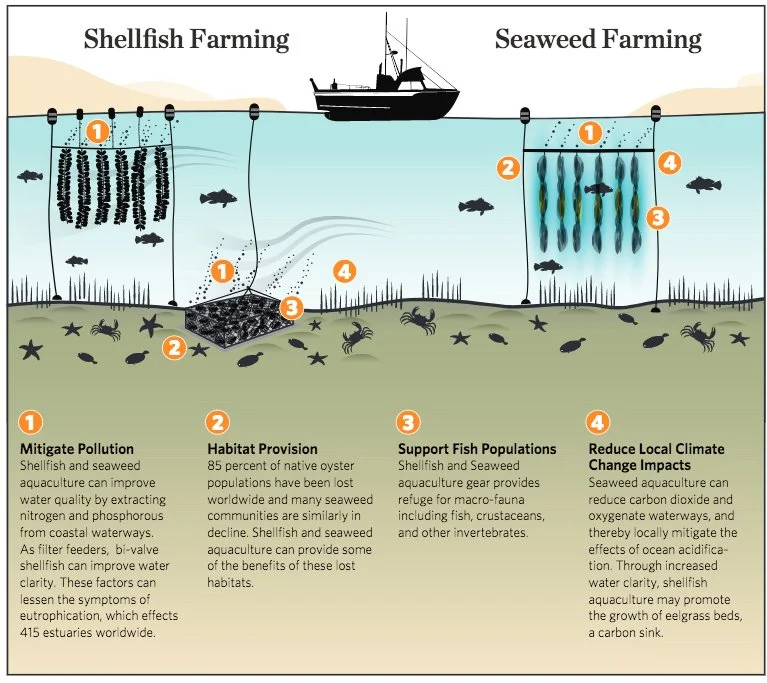

Benefits of Aquaculture Ecosystems: Coastal ecosystems are threatened by coastal pollution, habitat loss, and overfishing, and are further exacerbated by climate change. When conducted appropriately and in appropriate locations, commercial aquaculture can accelerate ecosystem recovery while providing sustainable seafood and green jobs in coastal communities.

Source: The Nature Conservancy

Aquaculture and Consumer Choices

As the world faces climate change, a growing population, and declining wild fish stocks, well-managed aquaculture is an important way to feed people and protect aquatic ecosystems.

Aquaculture—the farming of fish, shellfish, and seaweeds—now provides nearly 60% of the world’s seafood, playing a critical role in global food security while easing pressure on wild fisheries. Operations range from freshwater ponds and coastal net pens to advanced land-based recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). Farmed species include salmon, tilapia, catfish, oysters, mussels, and seaweeds, reflecting the sector’s rapid growth and technological diversity.

Aquaculture systems are tailored to species and environments. Freshwater fish are commonly raised in ponds or tanks, while salmon are often grown in coastal or offshore cages. RAS facilities filter and reuse water, allowing precise control of water quality and reducing environmental risk. Shellfish are cultivated on racks, bags, or longlines and naturally filter water, while seaweed farms provide food and materials while absorbing excess nutrients and carbon.

When responsibly managed, aquaculture delivers affordable, protein-rich food, supports about 22 million jobs worldwide, and can contribute to habitat restoration and shoreline protection. Challenges remain—poorly managed farms can cause pollution, disease, and harm to wild species, and some systems require high investment and strong regulation. Ongoing advances in science-based practices, technology, and integrated farming are helping reduce impacts, improve efficiency, and position aquaculture as a cornerstone of a sustainable global food system.

Consumers also play a critical role in protecting ocean health. Growing awareness of overfishing has led many people to choose sustainable seafood—or to reduce seafood consumption altogether. Sustainable choices favor fast-growing, resilient species such as sardines and anchovies over slow-growing, vulnerable species like orange roughy. Looking for labels from certification programs such as the Marine Stewardship Council and Friend of the Sea, along with consumer guides like the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch, helps shoppers make informed decisions. At a global scale, transparency tools such as Global Fishing Watch track fishing activity worldwide, empowering individuals to support responsible fisheries and encouraging greater accountability across the seafood industry.

Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) follows government standards for sustainable fishing and grants its eco-label, which demonstrates that the product was harvested in a well-managed, sustainable manner. Friend of the Sea is a International Programs for the Dolphin-Safe Tuna program, and as a project of the Earth Island Institute. Global Fishing Watch provides open data on human ocean activity to promote fair, sustainable use. They use advanced technology to provide transparency and protect the ocean for everyone's benefit.