Mangroves

Mangroves make up less than 2% of marine environments but account for 10-15%

of carbon burial. A one-kilometer-wide mangrove forest can reduce the

destructive force of hurricanes, cyclones,

and tsunamis by up to 90%.

Photo Credit Stockcake

A mangrove passage near Everglades City, Mangrove forests such as this one are rapipidly pushing north along Florida coaslines. Photo credit Sarasota Herald-Tribute

Mangroves: The Forests We Almost Erased and Why We Cannot Afford to Lose Them

Mangrove forests are among the most important ecosystems along the world’s coastlines, playing a vital role in both environmental stability and climate regulation. Classified as “coastal blue carbon” ecosystems, mangroves function as powerful natural carbon sinks. They capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it within their dense plant tissues and deep, waterlogged soils. This long-term carbon storage makes mangrove forests essential allies in mitigating climate change, despite their relatively small global footprint.

Although seagrass meadows, salt marshes, and mangrove swamps occupy only about 0.2% of the seafloor, they are responsible for sequestering more than half of the ocean’s carbon. Mangrove forests are particularly efficient: per acre, they can store up to four times more carbon than tropical rainforests. While mangroves make up less than 2% of marine environments, they account for an estimated 10-15% of global carbon burial, highlighting their disproportionate impact on Earth’s carbon cycle.

The carbon-storage capacity of mangroves is striking even at the smallest scale. A single acre of mangrove forest can store approximately 1,450 pounds of carbon each year, roughly equivalent to the emissions produced by a car driving nearly 6,000 miles, across the United

States and back. When mangroves are destroyed, this stored carbon is released into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change rather than slowing it.

Beyond their role in climate mitigation, mangrove forests provide critical protection against extreme weather. Their dense, interlocking root systems act as natural barriers, absorbing and dispersing

%wave energy from storms. Research shows that a one-kilometer-wide mangrove forest can reduce the destructive force of hurricanes, cyclones, and tsunamis by up to 90%. As climate change intensifies storms and raises sea levels, this protective function becomes increasingly essential for coastal communities.

Despite their immense value, mangrove forests have been lost at an alarming rate, between 20%

and 35% globally over the past 50 years. This loss represents not only the destruction of a

unique ecosystem but also the removal of one of nature’s most effective tools for climate

resilience and coastal protection. Preserving and restoring mangrove forests is therefore not just

an environmental priority, but a critical investment in the future stability of both coastal ecosystems

and human societies.

At the boundary where land dissolves into subtropical and tropical seas, mangroves take root in

places few other trees can survive. These resilient forests thrive in low-oxygen soils, bathed daily

by tides and surrounded by slow-moving waters that allow fine sediments to settle. For centuries, mangroves quietly performed their work, stabilizing coastlines, sheltering wildlife, and supporting human communities. Yet for much of the 20th century, they were misunderstood, dismissed

as mosquito-infested swamps unworthy of protection.

Before 1970, mangroves were widely viewed as obstacles to progress. Clearing them seemed harmless, even beneficial. As a result, destruction accelerated at an astonishing rate. According

to the United Nations, nearly 14,000 square miles of mangrove forests were destroyed between

1980 and 2005, leaving fewer than 60,000 square miles worldwide by the mid-2000s. Trees were

harvested for timber, wetlands were filled to control mosquitoes, and vast areas were converted

into shrimp farms or reclaimed for development. What was lost, however, was far more valuable

than the land that replaced it.

Mangroves are some of the most biologically rich ecosystems on Earth, supporting over 1,500

species, including tigers, sharks, manatees, and sloths. Yet 15% of these species now face extinction.

Beyond wildlife, mangroves protect coastlines by absorbing wave energy, trapping sediments, and filtering nutrients, which also helps nearby coral reefs and seagrass beds survive. They are powerful carbon sinks, storing 2-4 times more carbon per acre than terrestrial forests. When destroyed, this carbon is released, worsening climate change. A single acre stores about 1,450 pounds of carbon annually, roughly the emissions from driving across the United States and back.

Mangroves also shield communities from rising seas and storms. A one-kilometer-wide forest can reduce wave energy by up to 90%, protecting human lives better than many concrete seawalls.

Once dismissed as worthless swamps, mangroves are now recognized as vital for biodiversity,

climate, and human safety. The challenge is clear: protect what remains, restore what has been

lost, and let these forests continue safeguarding life at the edge of land and sea.

In 1991, a powerful cyclonic storm made landfall in an area of Bangladesh where the mangroves had been stripped away. The 20-foot (6-meter) storm surge, comparable to the height of Hurricane Katrina’s, contributed to the roughly 138,000 people killed by the storm

(for comparison, Katrina killed 1,836). The damage caused by the 2004 tsunami spurred

impacted countries to rethink mangrove importance, and many restoration projects are

working to rebuild lost forests.

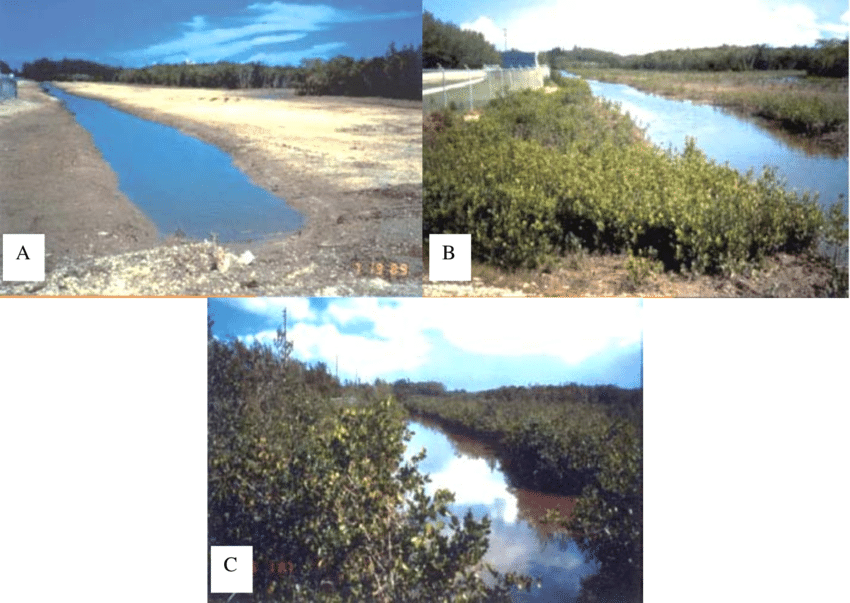

Photographs showing a time series of a restored mangrove at West Lake Park, Hollywood, Florida, USA. The channels were restored by grading the site to match the slope of an adjacent relatively undisturbed mangrove wetland and constructing tidal creeks. No planting of mangroves occurred, and all three Florida mangrove species established naturally on their own (Lewis, 1990, 2005). (A) initial completion of grading and construction of tidal creeks (July, 1989), (B) after 28 months, and (C) after 78 months (photos by Dr. Roy R. Lewis III).

Case Study: West Lake Park near Ft. Lauderdale, Florida.

In 1986, ichthyologist Robin Lewis worked to restore 1,300 acres of mangroves at West Lake Park near Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where about 200 acres were completely dead, covered in dirt while invasive plants thrived.

Lewis concluded that traditional mangrove restoration resembles forest planting. He cultivates seedlings in greenhouses, relocating them to mudflats, but this is often ineffective. For instance, the World Bank spent $35 million planting nearly 3 million seedlings in the Central Visayas from 1984 to 1992; by 1996, fewer than 20% survived. Many global mangrove restoration efforts fail because wetland environments are dynamic, and seedlings struggle if water levels aren't ideal.

Typically, plantings use only one mangrove species, unlike the diverse habitats found in natural mangrove forests. “Mangrove forests consist of diverse trees and communities, showcasing complexity. Single-species plantings result in simpler habitats that support less biodiversity.”

Lewis began restoring a ten-acre plot with a hydrologist to map the water flow. After three years, he initiated the complete restoration project, which required significant dirt relocation. With bulldozers, he shaped a gentle slope for tidal flow. By 1989, the site looked barren, but by 1991, seedlings took root, and by 1996, Florida’s three mangrove species were established. A survey revealed as many fish and aquatic species as in a nearby healthy mangrove site, attracting shorebirds.

“There wasn’t a single mangrove planted in the whole project,” Lewis said. “Mother Nature can repair herself if given the opportunity.” His methods have revived 30 mangrove sites in the U.S. and been adopted in 25 countries, including Thailand and Indonesia. This work requires careful planning, study, and patience but is vital for restoring the world’s mangroves.

A threat and a solution – tourism’s role in mangrove protection. From the Race to Resilience Race to Zero website.https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/a-threat-and-a-solution-tourisms-role-in-mangrove-protection/

Florida mangroves mitigated flood damage

The Nature Conversancy reported in 2017, mangroves in Florida mitigated flood damage from Hurricane Irma by nearly 25%. A study by scientists from the engineering, insurance, and conservation sectors found that mangroves prevented $1.5 billion in direct flood damages.

Mangroves also protected over 626,000 people across Florida. Their effectiveness in reducing

flood risks increases with their abundance and placement in front of densely populated areas.

These vital ecosystems safeguarded over half a million residents and averted billions in losses

across counties such as Collier, Lee, and Miami-Dade. They helped avoid about $802 million in

losses, along with an additional $580 million. Furthermore, mangroves shielded valuable coastal properties from more than $134 million in potential flood damage.

Case Study: Tahiry Honko, Madagascar Mangrove Carbon Project

The Tahiry Honko project in southwest Madagascar is one of the largest mangrove restoration initiatives in the world. In the Velondriake Locally Managed Marine Area, ten villages work together

to protect over 1,200 hectares (3,000 acres) of mangroves, addressing degradation caused by harvesting for firewood and building materials.

The project generates carbon credits and sustainable income for local communities while

fostering conservation, reforestation, and alternative livelihoods like seaweed farming, sea

cucumber cultivation, and mangrove beekeeping. It prevents nearly 1,400 tons of CO2 emissions

each year, with revenues supporting community services and LMMA management. The Plan Vivo Foundation has validated the project, giving confidence to investors such as the Darwin Initiative, GEF, MacArthur Foundation, and UK Aid.

For over 15 years, Blue Ventures has partnered with local communities to protect mangroves, preserving vital carbon stores and preventing emissions. This project demonstrates how locally

led conservation can safeguard ecosystems, support livelihoods, and fight climate change. The loss

of mangroves would threaten both human communities and the global climate.