Kelp Forests:

Pillars of Coastal Oceans and Human Communities

Kelp forests are dense underwater ecosystems of large brown algae (kelp) in cool,

nutrient-rich coastal waters, functioning like forests on land by providing food, shelter, and protection for thousands of marine species, from tiny invertebrates to sea otters, seals, and whales, while also absorbing carbon dioxide and supporting fisheries, though they face threats from ocean warming and pollution.

Kelp Forests: Pillars of Coastal Oceans and Human Communities

Kelp forests are among the most productive and dynamic ecosystems on Earth. Found along cool, nutrient-rich coastlines, these towering underwater forests are built by large brown algae that can grow more than a foot per day under ideal conditions. Though they occupy a relatively narrow band

of the global ocean, kelp forests play an outsized role in supporting marine biodiversity, sustaining fisheries, buffering coastlines, and providing benefits that extend directly to human societies.

Global Distribution and Environmental Requirements

Kelp forests occur primarily along temperate and subpolar coastlines, including the Pacific coasts

of North and South America, southern Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of the North Atlantic. Their distribution is tightly constrained by environmental conditions. Kelp requires cool water temperatures, ample sunlight, hard substrates for attachment, and a steady supply ofnutrients—often delivered by coastal upwelling.

Because kelp thrives near the edge of its thermal tolerance, even small increases in ocean temperature can dramatically reduce growth and survival. Marine heatwaves, such as those increasingly observed over the past decade, have pushed kelp forests beyond these limits in

many regions, leading to widespread losses.

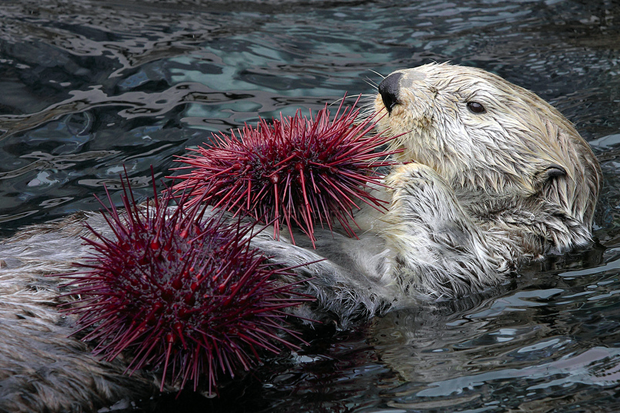

Predators, Grazers, and the Balance of the Food Web

Kelp forest health depends not only on physical conditions but also on ecological balance, particularly predator-prey relationships. Sea urchins are the primary grazers of kelp. When kept in check by predators such as sea otters, sunflower sea stars, and certain fish species, urchins play a normal

role in trimming kelp growth.

However, when predators decline due to disease, overfishing, or climate stress, urchin populations can explode. In these cases, urchins overgraze kelp holdfasts and blades, transforming lush forests into “urchin barrens,” rocky sea-floors with little remaining vegetation. Once established, these barrens can persist for years or even decades, as dense urchin populations prevent kelp from

reestablishing.

This dynamic illustrates a key ecological principle: kelp forests are regulated by top-down control.

The loss of predators can trigger cascading effects throughout the ecosystem, fundamentally

altering habitat structure and biodiversity.

Importance to Marine Ecosystems

Kelp forests function as ecosystem engineers. Their tall, flexible fronds slow currents and dampen wave energy, creating calmer conditions beneath the canopy. This structure provides shelter,

nursery habitat, and feeding grounds for hundreds of species, including fish, invertebrates,

seabirds, and marine mammals.

Primary productivity in kelp forests rivals that of tropical rainforests. Through photosynthesis, kelp converts sunlight and dissolved nutrients into biomass that fuels complex food webs. Even when kelp tissue breaks off and drifts away, it continues to support life, delivering organic matter to deep-sea ecosystems and adjacent habitats.

Kelp forests also improve water quality by absorbing excess nutrients and carbon dioxide, helping moderate local ocean chemistry and reducing the intensity of coastal acidification.

Support of Fisheries and Coastal Economies

Healthy kelp forests are closely linked to productive fisheries. Many commercially important species depend on kelp forests during at least part of their life cycle. Juvenile fish, in particular, rely on the dense structure of kelp for protection from predators.

By sustaining fish populations, kelp forests indirectly support fishing communities, seafood supply chains, and coastal economies. Their loss often coincides with declining fishery yields, highlighting the connection between ecosystem health and human livelihoods.

Beyond fisheries, kelp forests contribute to tourism and recreation. Diving, snorkeling, kayaking,

and wildlife viewing in kelp-rich regions generate substantial economic value while fostering public appreciation for marine conservation.

Human Uses and Emerging Benefits

Humans have used kelp for centuries as food, fertilizer, and raw material. Today, kelp is harvested

and cultivated for a wide range of applications, including food products, animal feed, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and agricultural supplements. Interest in kelp farming is growing as a potentially sustainable form of aquaculture that requires no freshwater, fertilizer, or arable land.

Kelp is also being explored as a climate solution. While not a silver bullet, kelp forests store carbon

in biomass and sediments and may contribute to localized climate mitigation and adaptation, especially when combined with broader emissions reductions and conservation efforts.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite their value, kelp forests are under increasing threat from climate change, predator loss, coastal pollution, and physical disturbance. Warming oceans, more frequent marine heatwaves,

and shifting species interactions are pushing many kelp systems toward collapse.

Protecting and restoring kelp forests requires an ecosystem-based approach: reducing greenhouse gas emissions, conserving predator populations, managing fisheries sustainably, improving water quality, and supporting active restoration where natural recovery is unlikely.

Kelp forests remind us that marine ecosystems are not only biologically rich but deeply connected

to human well-being. Their future, and ours, depends on maintaining the delicate balance that

allows these underwater forests to flourish.