Estuaries:

Where Rivers Meet the Sea and Life Thrives

An estuary is a vital, partially enclosed

coastal ecosystem where freshwater from rivers mixes with salty ocean water, creating brackish water and highly productive habitats

for fish, birds, and plants, acting as nurseries, feeding grounds, and storm buffers, though

they face threats from pollution, climate

change, and coastal development. These

unique environments, ranging from bays and lagoons to fjords, support rich biodiversity and provide essential services like water filtration

an coastal protection

At the edge of continents, where freshwater rivers slow and spread into the ocean’s reach, estuaries form one of Earth’s most dynamic and life-giving ecosystems. Here, tides pulse twice daily, salinity shifts with every storm and season, and sediments carried from far inland finally settle. These places are neither fully marine nor fully terrestrial, but something richer, more complex, and more productive than either alone.

Estuaries are transition zones, ecological crossroads where land, river, and ocean converge. Though they occupy a relatively small fraction of the planet’s surface, they support an outsized share of biodiversity and provide essential benefits that ripple outward to coastal seas, inland watersheds,

and human communities alike.

A Landscape in Constant Motion

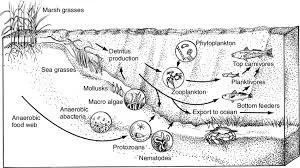

Estuaries are shaped by movement. Freshwater flows downstream carrying nutrients, organic matter, and sediments from forests, farms, and cities. Saltwater pushes inland with the tides, bringing marine plankton, larvae, and dissolved minerals. The result is a constantly shifting mosaic of habitats. Mudflats exposed at low tide, submerged channels at high tide, salt marshes flooded and

drained daily, and brackish waters where salinity can change by the hour.

This variability might seem hostile, but for life adapted to it, estuaries are ideal. Few environments

on Earth concentrate so much food, shelter, and opportunity in one place. The mixing of fresh and saltwater fuels plankton blooms, which form the base of complex food webs that extend both

offshore and onto land.

Nurseries of the Sea

Estuaries are often called the “nurseries of the ocean,” and for good reason. Many commercially and ecologically important marine species begin life here. Juvenile fish, crabs, shrimp, and shellfish find refuge in shallow, food-rich waters where predators are fewer and growth is rapid.

Salt marsh grasses, seagrass beds, oyster reefs, and mangrove edges create intricate structures that provide hiding places and feeding grounds. A young fish that survives its early months in an estuary may later migrate to coastal waters or the open ocean, carrying the benefits of estuarine productivity far beyond the shoreline.

Because of this role, the health of offshore fisheries is tightly linked to the condition of estuaries. When estuaries thrive, marine ecosystems hundreds of miles away often do as well.

A Bridge to the Land

Estuaries are just as vital to terrestrial ecosystems. Along their edges, wetlands and tidal marshes form green buffers between land and sea. These areas absorb floodwaters during storms and heavy rains, reducing damage to upland forests, farmland, and human settlements. Instead of rushing

inland as destructive surges, water spreads out and slows, losing its force among grasses

and roots.

For wildlife on land, estuaries are oases. Migratory birds depend on estuaries as rest stops along global flyways, feeding on abundant invertebrates and fish during long journeys. Mammals forage along tidal edges, while insects emerging from estuarine waters feed birds and bats farther inland, transferring nutrients from water to land.

Even plants benefit. Estuarine wetlands trap sediments and nutrients, enriching soils and

helping stabilize shorelines. In doing so, they prevent erosion that would otherwise strip land

away grain by grain.

Nature’s Water Filters

As rivers deliver nutrients from upstream landscapes, estuaries act as ecological checkpoints. Wetland plants, microbes, and filter-feeding animals remove excess nitrogen, phosphorus, and pollutants before they reach the open ocean. This filtration reduces the risk of harmful algal

blooms and oxygen-depleted “dead zones” offshore.

Sediments carried downstream, often laden with contaminants, settle out in estuaries instead of smothering coral reefs or seagrass meadows farther out to sea. In this way, estuaries protect marine ecosystems while simultaneously improving water quality for coastal communities.

Powerhouses of Carbon Storage

Estuaries play a quiet but critical role in regulating Earth’s climate. Their wetlands, salt marshes, mangroves, and seagrass beds, are among the planet’s most effective natural carbon sinks. Plant material accumulates in waterlogged soils where low oxygen slows decomposition, locking carbon away for centuries or even millennia.

This “blue carbon” storage helps offset greenhouse gas emissions while also building soil elevation, allowing wetlands to keep pace, at least in part, with rising sea levels. Protecting and restoring estuaries is therefore both a climate mitigation and climate adaptation strategy.

Fragile Abundance

Despite their productivity, estuaries are highly vulnerable. Their position at the end of watersheds makes them collectors of everything that happens upstream: pollution, excess nutrients, altered river flows, and sediments. Coastal development, dredging, and shoreline hardening can fragment habitats and disrupt natural tidal movement. Climate change adds further stress through sea-level rise, stronger storms, warming waters, and shifting salinity patterns.

When estuaries degrade, the losses cascade. Fisheries decline, water quality worsens, shorelines erode, and both marine and terrestrial species lose critical habitat.

Restoring the Crossroads

Across the world, restoration efforts are underway to revive damaged estuaries. Reconnecting rivers to floodplains, removing barriers to tidal flow, restoring wetlands, and rebuilding oyster reefs are helping estuaries regain their natural functions. These projects often deliver rapid returns: clearer water, increased wildlife, reduced flooding, and stronger coastal resilience.

Estuaries remind us that boundaries are not barriers, they are places of exchange, creativity, and resilience. Where river meets sea, life flourishes through connection. Protecting these ecosystems means safeguarding the link between land and ocean, ensuring that both continue to sustain one another in a rapidly changing world.