The Climate Awakening:

From Awareness to Action

Hurricane Florence viewed from the International Space Station in 2018. The eye, eyewall, and surrounding rainbands are characteristics of tropical cyclones. Flooding from Hurricanes Flo and Matthew damaged 75,000 structures in North Carolina.

Photo: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

Smoke from wildfires in Canada caused New York City’s sky turn orange, leading to hazardous air quality affecting millions in 18 states and 13 provinces and territories in Canada in June 2023.

Photo: Shutterstock

Hurricane Sandy caused the Holland Tunnel to flood in New York City, causing $70 billion in damages and killing 254 people in eight countries, from the Caribbean to Canada, in October 2012.

Photo: Fox New Weather

The Quiet Journey of Climate Understanding

My journey of awakening start on a summer afternoon in 2014, while flying the air over the Pacific Northwest the sky had turned an unsettling shade of orange. Smoke from British Columbia wildfires hundreds of miles away blotted out the sun, coating cities in ash and turning daylight into dusk. For many residents of New York City, it was the first moment climate change stopped being an abstract idea, and hundreds of people sought care for asthma attacks in local emergency rooms. The smoke led to hazardous air quality affecting millions in 18 states and 13 provinces and territories in Canada in June 2023.

For others, it was Super Storm Sandy that devastated New York City in 2012 with massive storm surges and winds, causing widespread flooding, killing 43 in NYC, knocking out power to two million people, destroying homes and damaging tens of thousands, crippling transportation by flooded tunnels and subways, and leading to $19 billion in damages and economic losses. The storm highlighted vulnerabilities in coastal areas such as the Rockaways and Coney Island, prompting massive recovery/resilience efforts.

Scientists are finding clearer links between hurricane damage and human-caused climate change. For instance, climate change made 80% of Atlantic hurricanes from 2019 to 2023 stronger, often pushing them into higher categories. In some storms, like Hurricane Milton, nearly half the damages were tied to climate change. Sea-level rise alone caused billions in extra damage. Looking at the 20 biggest storms since 2005, about half the total damage may be due to global warming. Overall, climate change means heavier rain, higher storm surges, and faster, more dangerous hurricanes—leading to bigger risks and costs for everyone.

Moments like these mark a turning point in how people understand the planet’s changing climate. But awareness does not arrive all at once. It unfolds gradually, shaped by emotion, experience, and understanding. Scientists, educators, and psychologists increasingly describe this evolution as a series of seven stages that trace the human journey from basic ecological awareness to a deeper, systems-level understanding of the forces reshaping Earth.

A Nation Awakening to a Warming Reality

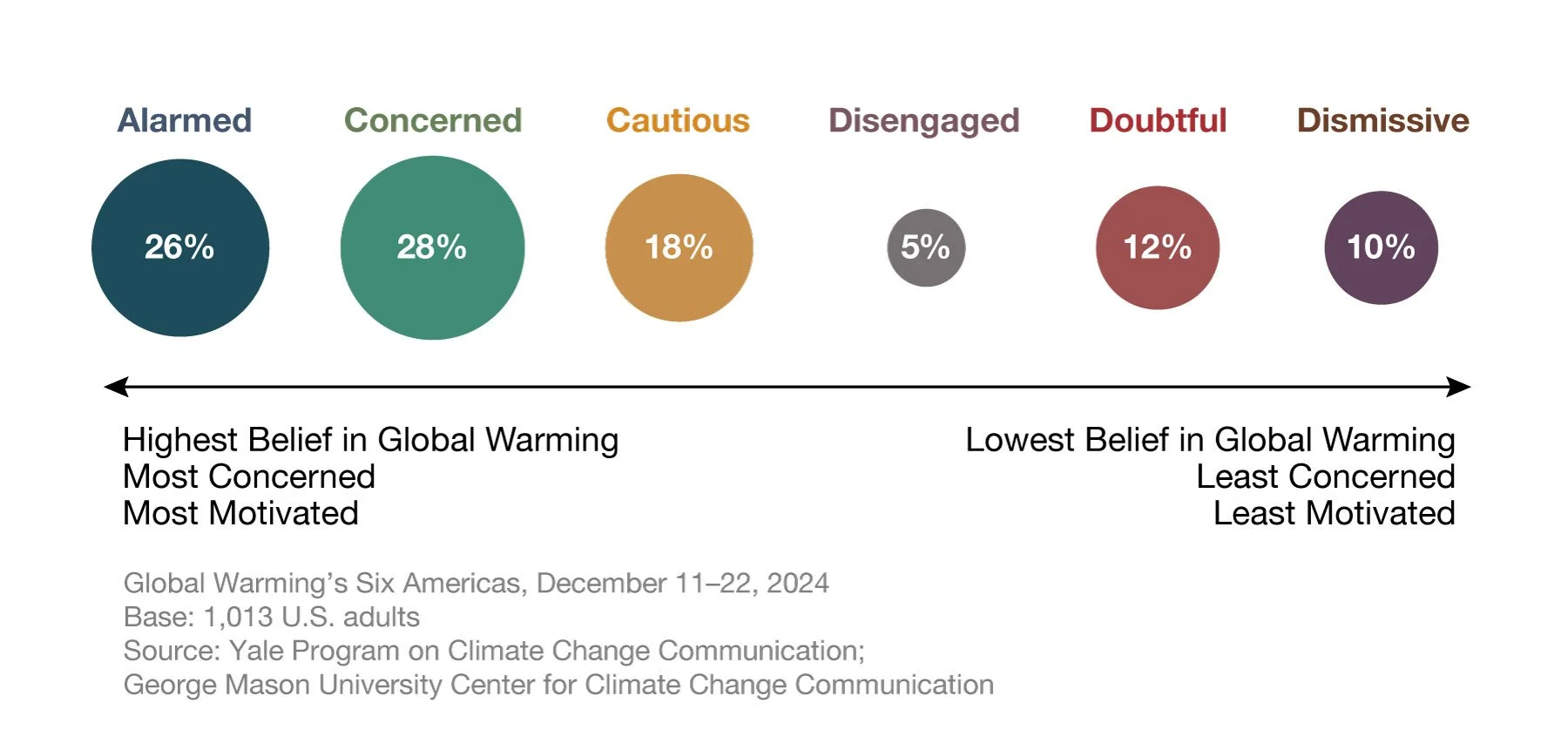

Recent polls from Yale’s Program on Climate Change Communication and Gallup show that most Americans now recognize global warming as real — and personal. Nearly 70% believe it’s happening, with believers outnumbering skeptics more than five to one

For years, climate change lived at the edges of American awareness—acknowledged by scientists, debated by politicians, and often distant from daily life. That distance is shrinking. According to the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, public understanding of climate change has reached its highest levels since national tracking began, driven largely by lived experience with extreme weather and rising costs of living.

As of 2025, nearly 72 percent of Americans believe global warming is happening, a record high. More than half—about 60 percent—understand that human activity is the primary cause, while another quarter attribute warming to natural cycles. The shift reflects a growing alignment between scientific consensus and public belief, even as gaps in understanding remain.

Yet the story of climate awareness in the United States is not uniform. Yale’s Climate Change in the American Mind project reveals meaningful differences in perception across racial and ethnic groups—differences shaped by geography, economic vulnerability, and lived experience.

Climate Awareness Across Communities

Communities of color consistently report higher levels of concern about climate change than white Americans. According to Yale’s findings, Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely than white Americans to believe global warming is happening, and more likely to say it poses a serious threat to their communities.

Farmers work to weed bell pepper fields in the sun as Southern California faced a heat wave in Camarillo, July 2024.

Photo: Etiennel Aurent/AFP

Hispanic Americans, in particular, show some of the highest levels of climate concern in the country. A strong majority report that global warming is already affecting their lives, often citing extreme heat, air quality, water scarcity, and rising food prices. Black Americans similarly report high levels of concern and a strong belief that climate change is harming vulnerable populations.

White Americans, while increasingly aware, tend to express lower levels of urgency on average. They are also more likely to underestimate the degree of scientific agreement on climate change. While nearly all climate scientists agree that human-caused warming is occurring, only about 58 percent of Americans overall recognize this consensus, a gap that persists across demographic groups.

These differences are not simply ideological. They reflect unequal exposure to climate risk. Communities of color are more likely to live in areas affected by urban heat islands, flooding, poor air quality, and infrastructure vulnerability—conditions that make climate change tangible rather than theoretical.

From Abstract Threat to Personal Reality

One of the most striking findings from Yale’s recent surveys is how many Americans now report personal experience with climate impacts. Nearly half of adults say they have already felt the effects of climate change, whether through extreme heat, wildfires, flooding, or severe storms.

This lived experience is reshaping public perception. About 65 percent of Americans now say they are at least somewhat worried about global warming, and nearly one in three say they are very worried. Climate change is no longer viewed solely as an environmental issue; it has become an economic one. The same surveys show that roughly two-thirds of registered voters believe climate change is affecting their cost of living, through higher energy bills, food prices, insurance costs, and disaster recovery expenses.

Still, a psychological gap remains. While most Americans believe climate change will harm future generations and ecosystems, fewer—about 46 percent—believe they themselves will be personally harmed. This disconnect highlights a lingering perception that climate impacts are unevenly distributed or delayed, even as evidence suggests otherwise.

A Cultural Turning Point

Taken together, the data reveal a country in transition. Awareness is high. Concern is rising. Experience is becoming personal. Yet understanding remains uneven, and urgency varies widely across communities.

What is clear, however, is that the old narrative of climate change as a distant or theoretical issue no longer holds. From wildfire smoke drifting across cities to heat waves straining power grids, the effects are increasingly impossible to ignore.

The Yale findings suggest that the United States is approaching a cultural threshold—one in which climate change is no longer a future risk but a present condition shaping daily life. How that awareness translates into action, policy, and collective responsibility remains the defining question of the decade ahead.

What is certain is this: the climate conversation in America has changed. The nation is waking up, not all at once, but steadily—one heatwave, one storm, one lived experience at a time.

The journey from climate change awareness to action is symbolized by a young Muslim girl holding an SOS for the Earth, reflecting the global youth movement inspired by Greta Thunberg. Through school walkouts and large climate strikes, young people are transforming concern into collective action, demanding climate justice. Rooted in stewardship, compassion, and accountability for future generations, this movement illustrates how faith, youth, and courage can turn awareness into impactful change. Photo: Shutterstock