Journey from Climate Change Awareness to Climate Action

Standing on a fallen log, we slow down and listen to the forest around us—wind, soil, and living systems working together. In that connection, we remember that caring for the climate begins with recognizing our shared place within nature. Credit:Oregon Adventure Coast

The transition from climate change awareness to meaningful climate action is often a deeply personal journey that begins with understanding but requires intention, courage, and consistency to sustain. Awareness alone—learning about rising temperatures, ecosystem loss, or climate-driven inequality—can provoke concern or even paralysis, but action emerges when that knowledge is connected to values, agency, and everyday choices. For many individuals, this shift happens when abstract global data becomes local and human: a flooded neighborhood, declining fisheries, rising food costs, or threats to personal health. From there, action takes shape through attainable steps—reducing consumption, changing diet or energy use, supporting restoration efforts, voting, or engaging in community advocacy—which reinforce a sense of efficacy rather than helplessness. Over time, individual actions often expand into collective ones, as people recognize that personal responsibility and systemic change are inseparable, and that sustained climate action is not a single decision but an evolving commitment to align one’s lifestyle, voice, and influence with the realities of a changing planet.

Stage One: A Connection to Nature

For most people, climate awareness begins with affection for the natural world. A childhood spent near forests or oceans. A love of hiking, fishing, or wildlife. A sense that nature is beautiful—and fragile.

At this stage, concern is emotional rather than analytical. People notice littered beaches, shrinking forests, or disappearing species. They may recycle or support conservation efforts, motivated by a desire to protect what they love. Climate change, however, still feels distant—something happening to polar bears or faraway ice sheets, not to daily life.

This stage is rooted in connection, not comprehension. It lays the emotional groundwork for everything that follows.

Stage Two: Recognizing a Global Problem

Eventually, awareness widens. Scientific reports, media coverage, and extreme weather events make it harder to ignore the pattern. Rising temperatures. Stronger storms. Longer droughts. Climate change begins to take shape as a real, global problem.

At this stage, people generally accept the science. They may know that carbon dioxide levels are rising or that fossil fuels drive warming. Yet the issue still feels abstract—important, but distant. Responsibility is often placed elsewhere: on governments, corporations, or future generations.

According to research from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, this is where much of the public remains: concerned, but unsure how the crisis connects to their own lives or choices.

Stage Three: When Climate Change Gets Personal

For many, understanding deepens when climate change stops being theoretical and becomes personal. A flooded basement. A ruined harvest. A heatwave that sends vulnerable relatives to the hospital. A wildfire season that no longer has an end. These experiences collapse the distance between global trends and individual lives.

This is often the stage where eco-anxiety takes root. People begin to worry not just about the planet, but about their health, finances, and future. The American Psychological Association describes this response as a rational reaction to environmental threat, not a disorder. Behavior often changes here—less waste, fewer flights, more conscious consumption. But beneath these actions lies a growing realization: individual effort alone may not be enough.

Edi

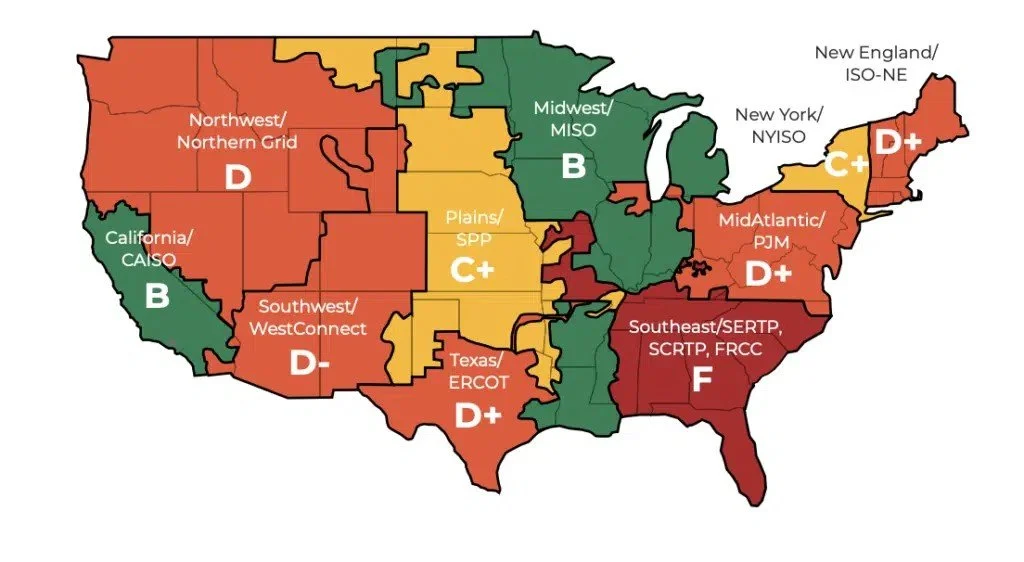

The American for a Clean Energy Grid assesses regional transmission planning in 2023. California and the Midwest/MISO score highest due to proactive planning. The Southeast has the greatest potential for growth, whereas the West (excluding California), the Mid-Atlantic (PJM), New England (ISO-NE), and Texas lag behind. Credit: Transmission Planning Development Regional Report Card.

Stage Four: Seeing the System

With time, awareness shifts outward. People begin to see that climate change is not primarily the result of personal failure but of systems designed around fossil fuels, endless growth, and resource extraction.

This is the stage of systems awareness.

Energy grids, transportation networks, industrial agriculture, global supply chains—these structures come into focus as the real drivers of emissions. Recycling suddenly seems small in comparison to coal-fired power plants or deforestation for global markets.

This realization can feel both empowering and unsettling. Empowering, because it clarifies where change must happen. Unsettling, because it exposes how deeply climate change is embedded in modern life. As systems theorist Donella Meadows once wrote, “The least obvious part of the system, its function or purpose, is often the most crucial.”

Stage Five: Energy Literacy

At the heart of the climate crisis lies a simple truth: it is an energy problem.

By this stage, people understand that the modern world runs on fossil fuels—and that decarbonization means transforming how energy is produced, distributed, and consumed. Electricity grids, transportation systems, building design, and industrial processes all become part of the picture.

This is where climate awareness becomes practical. People begin to understand why renewable energy matters, why electrification is essential, and why efficiency alone cannot solve the problem. The abstract concept of “emissions” becomes tangible, tied to power plants, pipelines, and vehicles.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, energy production accounts for more than three-quarters of global greenhouse gas emissions. Grasping this fact often marks a turning point from concern to informed engagement.

Stage Six: Interconnection and Justice

As understanding deepens, climate change reveals itself as more than an environmental issue—it becomes a social one.

People begin to see how climate impacts fall unevenly. Low-income communities face greater exposure to pollution. Coastal populations lose homes first. Farmers and Indigenous communities experience disruptions long before urban centers do.

This stage is defined by systems thinking. Climate change is no longer isolated from food security, public health, migration, or economic inequality. Everything is connected. Feedback loops emerge: warming accelerates ice loss, which accelerates warming. Deforestation alters rainfall, which disrupts agriculture.

The crisis is no longer just about carbon—it is about resilience, equity, and the future of human civilization.

Stage Seven: Purpose and Regeneration

The final stage is not despair. It is resolved.

Here, people move beyond fear toward purpose. They accept that the goal is not to preserve the world as it was, but to shape what comes next. Climate action becomes less about sacrifice and more about possibility—cleaner air, healthier cities, restored ecosystems, and more resilient communities.

This stage often brings engagement: voting, organizing, innovating, teaching, restoring land, or advocating for systemic change. The focus shifts from avoiding loss to building something better.

Rather than asking, “How do we stop climate change?” the question becomes, “What kind of world do we want to create?”

A Journey Still Unfolding

The Seven Stages of Climate Awareness reveal that understanding climate change is not simply a matter of facts. It is a human journey—shaped by emotion, experience, and evolving perspective. People move through these stages at different speeds. Some move forward, others stall or step back. But as climate impacts intensify, more people are being pulled into deeper awareness. The challenge now is not just to spread information but to guide understanding—helping societies move from recognition to responsibility and from fear to meaningful action. Because the climate story is no longer only about what is happening to the planet. It is about how humanity chooses to respond.